Chapter 23: Sojourn in Greece

Chapter 23

Sojourn in Greece

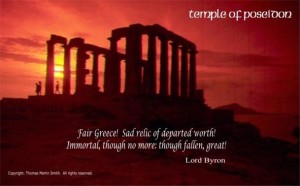

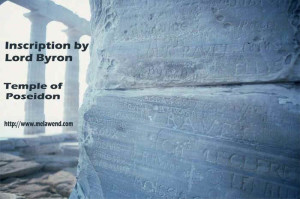

Fair Greece! Sad relic of departed worth!Immortal, though no more: though fallen, great!

Lord Byron Childe Harold’s Pilgrimage

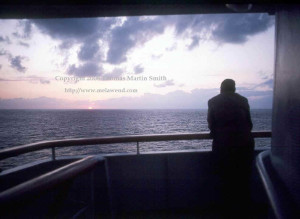

Early the next morning, there was a knock at our cabin door – a wakeup call for Dabney in the other upper birth. I lay in my bunk looking out the round porthole. During the night, we had crossed the Strait of Otranto, between the Adriatic and the Ionian Sea, and were now passing slowly along the northeast shore of Corfu. Homer praised the island’s beauty and it was the background for Shakespeare’s “The Tempest”. In the dim morning light, the island looked beautiful, like a mermaid lying on her side wearing sequins of lights. Corfu was indigo blue against a slightly lighter blue sea and a still lighter gray-blue sky. The pine trees and the rocky shoreline put me in mind of Vancouver Island (where I am now writing this story).

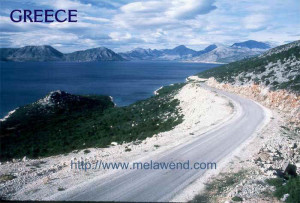

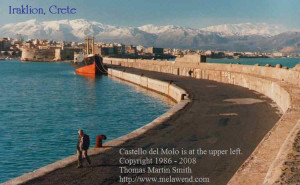

It seemed that backpackers were sleeping everywhere on the ship. I learned from a girl who was part of a group of students studying art in Greece that there had been a storm during the night. Many of the backpackers disembarked at Corfu. I walked the green-carpeted deck near the gold smokestack and sat on a white bench. I watched a now higher and sparsely treed shore as the Lydia slipped by it. My ticket would have me carried me to Patras but I decided to get off at Igoumenitsa, a mainland port near the Albanian border. The Lydia would not reach Patras until 5:00 p.m., rather late, I felt, to disembark and hunt for a campsite in a strange new land. Besides, I had already been enchanted by the rugged beauty of the shores of Greece and felt I would have missed a lot. A black-hulled tug named the Alexandros escorted us into port.

My map, put out by the Greek National Tourist Organization (GNTO), was difficult for me to follow. While there were a few explanatory notes in English, all place names were in Greek. Corfu, for example, was Kerkira , Crete was Kriti and Athens was Athina.

No matter. By ship, the coast of Greece had been beautiful to see; by scooter, it was awesome to experience. And my first image of a Greek came just outside Igomenitsa – a man burning twigs and branches in an orchard of ancient, gnarled olive trees. I thought of Dad and the clearing of our building lots – before the building of our last home together in Ridgeway and the cottage at Gooseneck Lake. The road went inland for a way and then returned to the coast.

Melawend and I rode along winding roads in drizzle through the coastal range of the Eprios Mountains. Where at last the road came back to the sea, I saw a hopeful sign – we were under a very large shelf of black clouds and you could see the bright edge of it on the southerly horizon, where we were headed. This gave the bare empty landscape in between a spooky, almost surrealistic atmosphere. This made me nervous. I shivered from the dampness. I wanted Grecian sunshine. It continued to drizzle through to Preveza.

I bought bread and chocolate cookies in a small bakery. A break in the land allowed the Ionian Sea and the Amvrakikos Kolpos to join. There was a short ferry ride between Preveza and Aktio that saved you from going the long circular route around the inland sea. I barely made it to the boat. People on board shouted, “Queek, queek!”

Goats ran across the otherwise empty road near Mitikas. Two rams were butting their heads on the roadside beside the dark blue sea. The goats would scamper with incredible ease up steep craggy slopes at the edge of the Akarnanika Mountains. The air grew warmer. The overcast sky broke and I looked under smoke-gray cotton-ball clouds out to a conical mountain on the small island of Kalamos. The mainland mountains were gray and brown rock, sparsely covered with rich green scrub and a few small trees. The soil of the foothills was orange-brown. This shore was devoid of humanity except for the odd truck that rumbled by. Greece was awesome in its lonely scenic splendor. And it was utter joy to roll through such seascapes on Melawend.

By now, Europe had overwhelmed me with its long, action-packed and overlapping histories. After all, I was from Europe’s offspring, North America. Our history – beginning with the European discoverers and colonizers – was short and thin: a mere few hundred years, covering a gargantuan and initially pristine landmass of 7,600,000 square miles. Ours had been largely a history of explore it, claim it and deal the natives off of it, overdevelop it and violate it with pollutants. We were the bold, industrious frontiersmen!

But then most of our forefathers had been raised on the old side of the Atlantic, where many torturous histories had made up the tapestry of their lives. Those histories covered a mere 1,900,000 square miles of territory (excluding the European parts of Russia and Turkey) but were measured in thousands of years. Being so close together, Europeans had always been pushing each other around – where else could they go? Colonies, of course! (And they were still going at it, though colonialism now took economic form through land purchases and asset grabs through corporate takeovers.) Europe was one convoluted mass of invasions, assimilations and rebellions – the rising and falling of empires. No wonder our North American forefathers and foremothers got the hell out of there! (And the natives of the new lands had so much less power to oppose invasion.)

Greece had seen waves of conquerors that included the Dorians, the Ionians, the Persians, the Romans, the Norman Crusaders, the Ottoman Turks, the Albanians, the Venetians, and the Egyptians. And now Melawend and I were riding in the wake of the ancient barbaric invaders (the Dorians) that took over western Greece.

The road left the sea and we rolled up and over the wooded mountains of Arcanania, coming back to the sea near Gulf of Corinth. We skirted Missolonghi where in 1824, Byron, after having taken up the cause of Greek independence and being appointed commander in chief of the Greek forces, succumbed to a recurrent fever and died. He had recently completed Don Juan, his epic satire of English society.

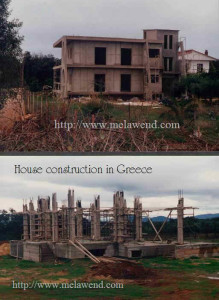

We were heading toward Patras, the third-largest city in Greece and the bustling port on the Gulf of Patras, near the Sea of Corinth. It was a rebuilt city as the Turks had completely destroyed it in the 1820’s during the Greek War of Independence. As I neared Andirro, where a ferry would take us to Patras, Melawend and I passed by a few new homes that were under construction. My father had been a residential developer and I had helped carpenters on a few of his projects, so I took a particular interest. As in Italy, what stuck me was the absence of wood. On the poured concrete foundation and floor of one house, forms of used wood planks and re-bars (reinforcing iron bars) stood like a decimated forest on the concrete floor. When the concrete inside was hard, the forms would be taken down and bricks and mortar would fill the spaces between the square columns of concrete to form the walls of the home. How I wished that my Dad was here so we could explore these Greek construction sites together.

I agonized over insurance – my coverage, bought in England, was to expire in a few days. I had to get to Athens quickly. Rushed again!

Prices here were cheap, however. I paid 50 cents for two loaves of bread and filled Melawend’s gas tank for $3.00, about half the price it was in Italy.

After riding over several rough patches of inadequately filled potholes, including one that could still have swallowed a Harley Davidson, (well, it was big) I would stop to record the bells of goats as they crossed the road. The goats would stare at me, pause and head way over to the far side. I was so enamoured with the beauty of this desolate coast that I often made like a mountain goat myself and scampered up the rocky slopes to take photographs. As I turned away from the sea, we came upon a huge bull that was strolling up the middle of the road. I gave him a blast on Melawend’s rather toyish horn but he paid no mind. I rode around him.

The land flattened out and was irrigated and I saw steel grain bins.

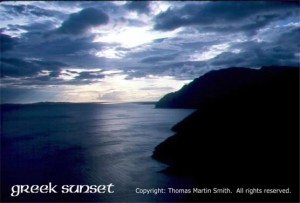

I reached the coast again just north of Andirrio. The road was high up on the coast and the sun was beginning to set beyond the headlands. A group of headlands cast a silhouette image of a monkey’s head lying in the water at the edge of the sea. It was a beautiful sight and I grabbed a few photos. I knew more spectacular light was coming and would render magnificent this seascape with a flotilla of gentle clouds overhead, but I had to find a place to camp. The road wound down toward Andirrio. Near the base, I found a muddy farm with olive trees. I rode up the driveway.

An old peasant woman in black was standing outside the house. I asked if I could camp. She spoke no English but she knew from my gestures what I was after. It was okay to camp here. I pulled Melawend off the gravel onto the ground around the trees. It had been ploughed but rain had smoothed it and weeds were growing up. Melawend sunk into the soft soil up to her hub, so I unloaded her on the spot.

I went up to the house and met a guy in his early thirties and a beautiful blond-haired girl with hazel eyes. They did not speak English but clearly motioned for me to bring my tent up closer to the house. I also understood that they wanted me to come in for coffee. A 60ish man and a skinny young guy with a bushy black beard came to the house as I was putting up the tent. He and the fellow in the house, both handsome men, looked like brothers. Another guy rode in on a scooter. I finished up and we all sat on the front porch. I was relieved that the guy with the bushy beard spoke English. He had worked on a ship for many years and had been to ports around the world, including ports in the US and Canada that were on the St. Lawrence River. He learned how to speak English during his travels. He had married a girl from South Africa and lived there for a few years.

The beautiful blond-haired girl brought me out a piece of apple cake with a cherry on top – it was delicious. The younger of the two brothers brought me some cognac. Everyone talked. When there was a language barrier, I would gauge acceptance of my presence by the amount of laughter I generated. I was obviously welcome here. But I talked mostly with the bushy-haired guy. Then they all got up to leave – only the old woman stayed. The bushy-haired guy said that if I needed any food, just come up to the house and ask. They got up to leave and I felt my shyness as I received several pats on the back as they made their way to their vehicles.

After they left, I found that I needed some drinking water, so I knocked on the front door. The old woman shouted something from inside. I thought she wanted me to go to the back door. I did. She shouted something else so I went back to my tent, grabbed my cameras and rode Melawend back up to that marvelous vista and got my sunset shots.

I marveled at how I had been in a cabin on a ship one night and found welcome on a muddy Greek farm the next – I seldom knew where I would spend a night when I traveled.

I awoke at 3:00 a.m. to the sound of a truck passing by. Then there was silence save for a soft breeze. I listened to my walkman and savored a Greek song, a ballad, I assumed, that a girl sang beautifully.

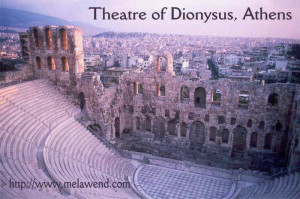

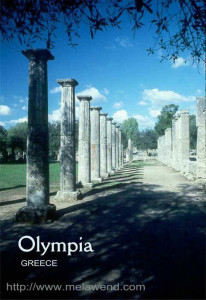

The next morning, Melawend and I boarded the ferry at Andirrio for the 10-minute ride to the Patras at the north end of the Peloponnesus. My objective was Olympia, birthplace of the modern Olympic Games, ancient hippodrome to the gods. Melawend and I rode on a modern highway and at Pirgos turned away from the sea. We rode through the mountainous hinterland and found Olympia nestled among trees in a remote valley. Olympia was not a town but a sanctuary for the ancient Greeks. Here, the ancients had built temples, altars, theatres, monuments, statues and a stadium.

The day was sunny and mild and there was the lightest of breezes, perfect for a stroll amid some ruins. It was pretty here and there were few tourists. Like the sites of most ancient ruins, Olympia had the look of a crumbling old cemetery. It rested peacefully amid trees against the backdrop of the low green mountains of Elis. But the buildings of Olympia were in rough shape. Most everything had tumbled down. Carved stones and blocks were scattered like the remaining debris of an earthquake. Other bits of buildings looked like they had been carefully laid over the grounds as if in a life-size jigsaw puzzle that you were supposed to assemble in your mind.

The most notable example of this was in the sacred precinct of Altis where I found the Temple of Zeus. I walked around on the mammoth square blocks of its foundation that also formed its floor. Next to the foundation were many huge fluted slabs of columns that had toppled over. They were lying rather neatly on the ground, leaning against each other like colossal cookies that had been gently poured out of a bag. People strolling among them looked tiny. The Olympian Games (that’s what they were called when this temple was new) were dedicated to the glory of Zeus, the supreme god of the ancient Greeks, and his temple was considered the centerpiece of Olympia. Inside it had stood one of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World – the 40-foot (12-meter) Statue of Zeus – made by the great Greek sculptor Phidias in about 435 BC. He fashioned the god’s robe and ornaments from gold and carved the body out of ivory. Now the Olympic Flame began its quad-yearly odyssey from this temple.

Next to the Temple of Zeus you found the ruins of the Heraeum, a temple dedicated to Hera, the wife of Zeus. In this oldest of Doric buildings there had been a table on which were the garlands that were prepared for the victors in the games.

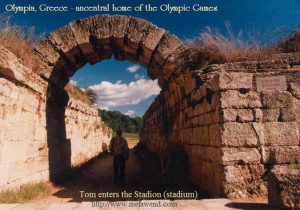

I focused in on the tremendously understated archway that led to the stadion, (the Greek word that gave us stadium). Really, you expected a far grander entrance – colossal statues of Adonis – something! This was just a simple narrow arch of badly weathered, tapered stones that seemed to hang in a state of imminent collapse over the entry to a small roofless corridor. On both sides of this stone passageway there was fill so that you had coarse tall weeds sprouting up around the ends of the arch.

I walked through this ancient passage that had been used by ancient athletes running into and out of the stadium. What a disappointment! (I was an idiot. I had not done any research prior to my arrival here.) I was expecting some grand amphitheater, an Olympian Colosseum – it was just an empty field of grass lined with some stone blocks! Banks of grass-covered fill and a bit of forest at the far end bordered the field. That was it! It was less impressive than many third-rate high-school track and field yards. But the Greeks gathered here to watch the most honourable of men compete in the footraces that began the second day of the games.

As I said in the prologue, I did not do a lot of research before I began my journey in part because I wanted to let the reality of a place work on me unimpeded by foreknowledge. Still, imaginings of a place heaped expectations on you. Olympia! Shrine of the Gods! Well, so much for shattered preconceptions based on imaginings. I was glad that I had grabbed up some brochures when I got here and now decided I had better sit down have a look at them. I assured myself that I would read more about all this when I got home.

Olympia was where it had all begun. The accepted date of the first Olympian Games was 776 B.C., when the name Nike referred only to the Goddess of Victory. But the victors then had it just as good as the endorsement-bestowed gold-medal winners of today – they likely lived out the rest of their days at public expense. Still, there was something hopeful in why the games had been created in the first place. Every four years, the Greeks interrupted their domestic wars to put on these competitions. City-states were invited to send their best athletes. The games had been held here for 1,000 years, even during the time of Roman domination. Imagine! But they ended because of increasingly bitter relations between Greeks and Romans. The games were buried in memory for 1500 years until they were exhumed in 1896 in Athens. They were revived by the efforts of a Frenchman, Baron de Coubertin.

The modern relay of the Olympic Torch began here at the placid ruins of the Temple of Zeus with the run to Berlin to begin the 1936 Olympics. The Nazis used those games to hype their might, and the games had certainly been used as a political pawn since then. Still, I was confident that the games born here would eventually help to win the day against man’s inhumanity to man.

In Olympia, I thought it was time to give the Olympic Games a new name. After all, though they were originally staged to honour a mythical god, they were more practically used to interrupt wars – to promote peace. I had not truly appreciated that. But what a fun way to exorcise our barbaric compulsion to conquer each other! It seemed better to cheer the athletic heroes of the playing fields rather than mourn the dead heroes of the battlefields. I thought, to hell with “War Games”! On with the “Peace Games”!

And, Why not hold them every three years instead of four?

In that optimistic mood, I took a gentler attitude toward Olympia, and to ruins in general. I walked about with a greater reverence for what this place symbolized. I left Olympia with a more hopeful outlook on my species.

At a leisurely 30 miles per hour, Melawend and I rolled in sunshine along the road between Olympia and Krestena. It was a nice country road and I saw lots of long-needledpine trees. There were donkeys bearing white bags that might have held grain or flour. Some of the donkeys bore men in dusty green or black overcoats. Small towns looked poor. We rolled past a small building called the Chicago Bar. Road signs were first in Greek, then a little further on you would see the sign in English.

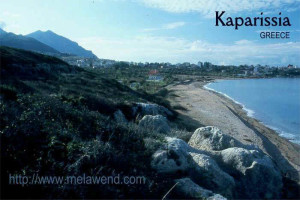

Home for the night was Camping Chani, at Kaparissia. In the men’s washroom, I met a young couple from the Netherlands. The guy had spent fourteen months working around North America. They were heading to Egypt and were planning to work their way around the world. He was tall, without an ounce of fat, and had typically blond hair and blue eyes. She was slim and beautiful with flawless tanned skin and the same color hair and eyes. They took a shower together, talking and laughing quite loudly as they made squishy, fleshy sounds. He came out wearing swimming trunks. She came out wearing only a flimsy clinging T-shirt that covered only the top half of her well-rounded bum. They didn’t care. I thought of how nice it would be to travel with Her. My attention was later drawn to two girls in a tent nearby.

The camp was closing up in two days. A middle-aged married couple owned it. He was also from Holland; she was from Sweden. Between 1970 and 1974, they made a trip by Land Rover through Arabia, Iraq, Iran and Afghanistan. They would visit communities, schools, and make reports to the Ministry of Education (the Netherlands). The Ministry had paid all their bills.

We talked about my journey.

“You will probably not be able to get a visa for the Sudan,” he said. “There is the civil war going on there.”

I retired to my camp by the sea and wrote notes under an olive tree. A cat visited me. I took a walk along the shore of the clear blue sea and took photos of the gravelly beach and the low scrubby headlands. This was “the life”: doing nothing and having such a peaceful place in which to do it.

I returned to my camp and started to pack up my gear, saving myself from some work the next morning. The two girls came over for a visit. Anette Kristoffersen and Pernille Hertz were from Holbaek, Denmark, near Stenile where the daughter of Marie’s uncle and aunt lived. They had recently graduated from high school. They were fascinated by Melawend and by tales of my journey so far. I took a photo of them as they signed the Odyssey Book. We wished each other well and they returned to their camp. For that brief time with Anette and Pernille, I was myself when I was seventeen and I felt those same hormonal urges. But I was twice their age and so was happy just for the brief cerebral visit with my younger days.

As darkness fell, I savoured what I considered would be my last night to relax in Greece. There was the soft sound of Mediterranean. The night sky was clear and full of stars. Some clouds creeped along the horizon. You could see lights on the sides of the mountains. This was a peaceful place.

(This was also very un-spooky Halloween (1986). It had been almost two months since Melawend and I rolled along the romantic shores of the Rhine. Shortly after midnight, as I was dozing off to the gentle sound of the Mediterranean Sea, firefighters near Basel, Switzerland, began battling a fire at a chemical warehouse of the Dandoz company on the Rhine. The Rhine would become a conduit for up to 30 tonnes of deadly poisons – herbicides, pesticides and mercury compounds. More than half a million fish and eels would be killed and the riverbanks contaminated, severely setting back a 10-year-old fish restoration effort. It would create a 28-mile (45-km) -long chemical slick that would drift northward in a 12-day journey to the sea.)

It was mild the next morning as I left. I had thought it was Sunday. It was Saturday. This gave me an extra day. On the road, I saw many signs that advertised Ouzo, the Greek liquor that Gerdi (the Baroness Von Kirchoff-Lintner) had told me about. When we came to Asprohorria, a little town just before the port of Kalamata, I saw a thickly treed lot. At least 20 white tents were pitched on it. There were lots of families but no vehicles. Clothes were hung from ropes.

Gypsies?

Along the road near Kalamata, I stopped to take a shot of small old house. It was white-painted stone and had a red tile roof. It lay on the other side a concrete bridge over a ditch. An old stone barn that stood to the right of the house drew my attention. It looked like a perfect cube, a little taller than the house. The whitewash on the stone was faded. Two windows had been filled with stone and left unpainted. But there was no roof. The two massive cracks in one of the barn’s walls should have told me something was wrong here.

Kalamata was the chief town of Messinia, an old but bustling and growing place. It had the 13th century Byzantine Church of Agii Apostili and a Frankish castle. In a convent, nuns made silks by hand. There was supposed to be good swimming at the beach. It was a city of old pastel buildings. But I knew nothing of what had happened here in mid-September.

As we rolled closer to town, I saw familiar advertising signs that included Fisher stereo, Levi’s jeans and Toyota cars. There were clotheslines on roofs. There were many more of those white tents but now they were in the yards of homes. I stopped at a supermarket. Inside, there was a variety of western goods including Dennis the Menace drinking glasses. The stock on food shelves was low. I picked up Q-tips, cookies, a protractor, two small coil notebooks and two tomatoes. No one spoke English. At the meat counter, I held up a 100-drachma note and pointed to the ham and then some gold-colored cheese. The butcher smiled and cut the right amount. The ham came to 117 drachma but he wrote 100 on the bag. You got no ends of meat rolls here; when cuts made for incomplete slices, they were thrown into a bin. I considered buying apples but I was wary of my lean budget. Bread of every kind was gone.

I looked around the open courtyard of another supermarket. Open-front shops had pull-down steel doors. The butcher shops here were red with hanging sides of beef and this reminded me of Papa Smith’s store in Ridgeway. At least two of the complex’s concrete support beams where buttressed with angled steel and wood braces.

We continued on and started to head out of Kalamata. There were still more white tents. I imagine it’s a fairly common design for tents, I told myself. And, as there were so many of them: Maybe a festival is about to begin. But I did not ask. And it was odd to even think that way because the atmosphere was very quiet, anything but festive. There was a swept-up, deserted look about the city.

My ignorance of the earthquake was shameful! And I regret it still. It is a tribute to the resiliency of people, as the citizens of Kalamata obviously possessed, that I had not truly noticed. It had struck on September 13th and measured 6.2 on the Richter scale. At least 19 people were killed and 300 had been injured. The quake had damaged about 70 percent of the buildings in Kalamata. (Was I blind? But then I wasn’t really looking – that was my affliction). The quake also leveled a nearby village. The next day, Premier Andreas Papandreou declared a state of emergency. Several aftershocks followed on the 15th, and 38 more people were injured. I had only a growing awareness that something wasn’t quite right here. This had made me nervous and reclusive and anxious to leave.

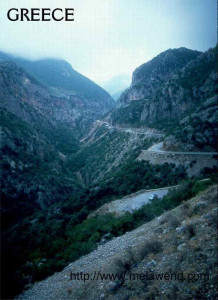

On the far side of Kalamata, Melawend and I rolled up into the mountains. These were very high. On the way up, you saw many olive trees. In the distance, you could see lower mountains that were rocky at the tops. There were palm fronds on ground. You could see the winding road as it ascended and you saw olive orchards that covered low mountains. You could see Kalamata and mountains that sloped to the sea.

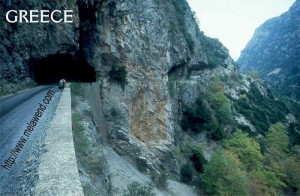

The green gave way to the brown of barren rock gorges. The road became precipitous. I had to be wary of steep drops and tight switchbacks. I stopped on the way to photograph a three-wheeled moto that was buzzing like an angry bee on its way up. There were more and more vistas. More photos. The road was rough in places. There were potholes and lots of rocks on the road from rockslides and there were holes in the pavement that were caused by large fallen rocks. I had difficulty talking and holding my little recorder as I weaved around all of this (not recommended).

The road to Sparta – above and below…

Finally the barren rock gave way to more greenery on the slopes. A pocket of autumn-colored trees, provided relief amid this desolate rugged dark land. I looked ahead and saw that we faced more climbing, right up to the clouds that were sweeping the mountaintops. We rode up and it was much cooler. We were heading up and up into those ominous-looking clouds. And then we were in them. I was freezing and wet but I began to notice that there were homes beside us in the mist. This was the high mountain village of Artemisia. We rolled on and the cloud began to glow a brilliant white. Then we broke through into glorious sunlight!

I felt more optimistic about things again and thought of how I would like to spend more time in each country, at least a month in each one. But my reverie was interrupted as we began to descend and the houses gave way to steep rock faces. We were riding down through a bleak canyon. There were tunnels and bends leading into tiny tunnels and unsupported cuts through steep rock faces. I felt like I was in Bedrock country and I would see the Flintstones around the next turn. The rock was shiny, coarse and extremely jagged. It finally started to level out. The air became warmer. I rode out of mountains and headed along a flat desolate road toward sunny edge of dark clouds, bound for Athens.

I rode into Sparta, which was the ancient enemy of Athens. Even in its heyday, in the 5th to 3rd centuries B.C., Sparta was little more than five simple villages in the easily defended valley of the Evrótas River. Art had flourished here but the Spartans developed a militaristic mind-set, led by the Spartiatai (descendants of the Dorian invaders) who were the class of rulers and soldiers who dominated the Peloponnesus. Rigid discipline and perfection were the order of the day. Deformed babies were murdered. Boys began military training at age seven and had to live in barracks until they were 30. All Spartans between ages 20 and 60 were compelled to serve as hoplites (foot soldiers). The Spartans eventually defeated Athens, ending the Golden Age of Greece, but they were in turn taken over by the Romans. Under the Goths, their city was destroyed. It was from their lifestyle that we describe austere ways as “spartan”.

Sparta was still a capital and it was still a small town. Many homes here had trees that had ripe oranges. I asked a lady at a gas station for directions to the road to Athens. She didn’t speak English and pointed in a doubtful direction. She probably just misunderstood me. I went the opposite way. I met two young guys at a corner.

“Athina?” I said.

They pointed in the direction I was headed.

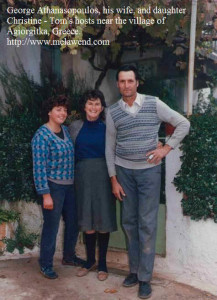

I planned to stop near Tripoli for the night but rode on to the village of Agiorgitka. On its outskirts, I saw a man who reminded me of the American actor, Alan Alda. He and a young boy were crouched as they repaired wooden apple crates beside the road. I stopped and with hardly a word, the man smiled and pointed to the small course plot near his house. He spoke no English but he seemed to understand “Toronto” when I said I lived near it.

It had rained here recently. I learned my lesson at the farm near Andirrio and unloaded Melawend on the asphalt road. I carried all my gear about sixty feet to a level spot on the weedy ground. Then I rode Melawend up to the site. As I was setting up, the man’s father (I guessed), his son and his daughter, a pretty girl with round features and dark brown hair, stood by the house and watched me set up my tent. This was the family of George Athanasopoulos.

(I was going to type here “a Greek look-alike for of Hawkeye Pierce” because many of you probably know “Hawkeye” of the TV series M.A.S.H., perhaps better than the real Alan Alda. Hawkeye had wit, charisma, deviousness, peeves, passion, compassion, strengths, weaknesses, an insatiable libido, and an unquenchable thirst, and an unshakable desire not to be where he was. He had created that immortal refuge from war: “the Swamp”. Hawkeye had flesh and blood and real character. And isn’t that the essence of a great actor – creating someone so real out of someone imagined.)

At their front door the next morning I would meet George, together with his daughter Christine, and his wife.

For now, I relaxed in my tent, eating the ham and cheese I had bought in Kalamata. Chickens ran loose around the farm. I heard sheep in the garage. A fat rabbit shared my food and kept me company just outside my tent. At dusk, George came out to the edge of the field. He smiled, waved and said with enthusiasm, “Good night!” I thought my presence provided the family with a novelty because he reappeared a few minutes later with his son and daughter. He gave me some bread and four apples that he identified by their Greek name. They looked and tasted like Golden Delicious apples. How strange and wonderful it was to now have the bread that I could not find and the apples that I could not afford to buy in Kalamata.

George smiled again and said, “Good night!”

I was lucky to have bread. I had discovered that bread bins in stores and bakeries were often empty by noon. I had ham, cheese, apples and peanut butter that I had diluted with added butter. And now I had apples. And I still had the small jar of mustard that Dianne had given me in Agincourt, way back in May. (She was right – mustard would keep a long time.) I pigged out on three open-face tomato, cheese, ham and mustard sandwiches followed by peanut butter.

I had learned to use my plastic basin when called by nature to do so. What to do? You gotta do what you gotta do, right? I dumped the aromatic contents by a row of trees. I looked up to a clear sky that was filled with stars. Looking up to the heavens, I imagined Greek astrologers of old. Were they now looking down on me for what I had just done?

I borrowed some batteries from my tape recorder and used my tiny flashlight to write a letter to Peter Gzowskiwho was the much-loved host of the CBC’s daily national call-in broadcast, Morningside. I was seeing so many wondrous things, albeit in cliché Europe, and meeting so many fantastic people that I still believed there might be some interest in some calls from the road for Morningside listeners across Canada. I reasoned this because I had met several people on this trip that were from across Canada and were interested.

(But I would never get a reply to this letter nor any other that I subsequently wrote to the CBC.)

In the morning it was foggy and cold. I heard a man singing in the distance. I heard church bells. My hosts met me at their front door, as I mentioned, and gave me a small cup of strong coffee. In my viewfinder, I framed them with the leafy greenery near their front door. Click. My flash surprised them because they burst out laughing after I took the shot. Perhaps they were not use to photography – film was expensive here (about $25.00 for 1 roll of 36 exposure print film). I thanked them and they waved heartily as Melawend and I rode away.

The road rose up again into low mountains. About 25 miles further on, I came upon a pull-off where there was a splendid view of a low conical mountain with wispy clouds feathering its shoulder. What made this sight dramatic was the foreground. There was a unique structure anchored to the coarse gravel. I had seen many of these in Greece. They looked like simple miniature one room churches of various shapes and sizes, made of steel and mounted on stilts that were imbedded in the ground at the side of the road. There were crosses atop the gable roofs. Inside there were usually pictures of Christ, some Apostles, incense burners, candles and spent matches. Some had pictures of people. This particular one had a little metal box presumably for monetary offerings. It had been locked but the lock had been pried off. I was told later that these were the sites of auto accidents where people had been killed. I imagined that somewhere, someone must have had a brisk business making these crude memorials.

AtKorinthos, we rode on a bridge high over the Corinth Canal, the deep, steep-walled trench that was cut through the Isthmus of Corinth in 1893, ending an arduous portage that went back to the time of ancient mariners. Traffic around the bridge was just too busy for me to stop and get a photograph. As a deterrent to future revolts between rival Greek city-states, the Romans had come to Corinth, killed its male population and sold its women and children into slavery.

I found a general store further on and bought cookies, bottled water, an apple muffin and round loaf of bread. I found a stony pull-off on the coast road and had a feast. As I munched and gulped, I looked out over sea and saw two fleets: one of islands and the other of commercial ships that were heading to and from the port of Piraeus.

I braced myself, for I was about to enter the bustling capital of Greece.

With my stomach full and my courage summoned, I mounted Melawend. We rode through increasingly industrialized areas. This was the industrial heartland of Greece – 50 percent of the country’s industries clung to the outskirts of the capital.

In the mid-afternoon, I spotted a campground about eight miles west of Athens. This was Camping Dafni, named after a nearby monastery. It was terraced and rocky with pine trees that were laden with cones. The nearby hills seemed barren. Just like Camping Roma, you heard the traffic of the main road but only in the front of the camp. I went into the office and met the manager. He was short and bald and he reminded me of several Italian Americans I had met in my time. It was about $10.00 per night to camp here. He was not enthusiastic about my staying for free, but he gave me one night.

I set up on one of the terraces. There were five caravans and only four other tenters here. The terraces went high up the side of a treed hill. There seemed to be room for a few hundred tenters and maybe a hundred caravans.

(The brochure on Attica campgrounds that I picked up later said that Camping Dafni had 310 sites, room for 600 people and was managed by Georgios Karabateas, but from his reluctant signature in my Odyssey Book later – you will understand his reason soon – I could not tell if the man I had met was, in fact, Mr. Karabateas.)

I saw a good-looking German couple coming out of a large luxurious caravan near my site. As in Kiparissa, I saw the uninhibited nature of northern Europeans as they walked over to the showers, wearing only small towels. I looked at the girl and felt my masculinity rising. I said to myself, What was my crime that I have to be alone so much? I took a cerebral cold shower and retired to my tent to rest.

The next morning, it was gray and mild. I packed up for my trip into Athens. As this would be my first entry into a city, I psyched myself up. I intended to follow the busses into Athens, just as I had in Rome. But something happened. In a flash, it altered the future of my journey. On our way down the curved paved lane, three stray dogs that had been sitting by the lane got it in their minds to chase us. No problem, just give Melawend a bit of throttle. But in looking at the dogs, I did not notice the gravel on the lane. The rear wheel slid under and Melawend slid off the lane and slammed into some trees behind the showers. Her rear wheel hit a tree. We were spun violently around until we hit another tree that stopped Melawend. I was thrown up and off Melawend, landing several feet away with the grace of a Gooney bird of Midway Island.

I lay on the ground with a burning sensation in my groin. I managed to get up and brush myself off. I lifted Melawend up and leaned her against a tree. Her rocker panel was dented, the right turn signal housing was cracked and the brake handle was now floppy. Otherwise, she was alright. The three dogs sat nearby, wagging their tails.

Though there were people in camp, no one came to see if I was okay. I began to walk Melawend back to the lane when I realized that something was terribly wrong. The pain became intense and I could hardly walk. I knew that the nature of my injury made my walk seem comical, but I didn’t give a damn what I looked like. It was all I could do make it over to the office and hoist Melawend onto her center stand. I knew I had been injured. I had to see a doctor, an expense I could ill afford.

(I was soon to learn a valuable lesson about pain.)

I limped over to the office and told the manager about the accident and then I asked if I could stay for four or five days. He seemed nervous, possibly worried that I would sue.

“I am not the director,” he said. “You are welcome to stay one night but tonight you must make registration.”

I sat in the office for a time. I called the embassy and was connected with a very kind woman who talked with me in the friendly and helpful way of Franca Mazzolani in Rome. This was Marie Economou. She said the embassy had already made appointments for me with officials of Athens, but she was most understanding about postponing them when I told her of the accident. She said they had a doctor on staff.

Thank God! Now if only I can get there.

“The unforeseen does not exist.”

That was what Phileas Fogg had said in Jules Verne’s Around the World in Eighty Days. And to that I would have said, “Bullshit!” Since that slippery ride into Dartmouth, back in Canada, the feeling that something painful was going to happen had often haunted me. The unforeseen did exist – especially if you aided it by imagining it! But how could you have prepared for something like this?

I had to leave Melawend behind. I staggered out to the bus stop and rode to the main terminal. I could hardly step out of the bus. No taxis stopped at the station. A man pointed over to a busy intersection where cabs congregated. I hailed about 15 taxis before I found a driver that spoke English. He had been a seaman for over 20 years and had visited 60 countries, including Canada.

He got me to the embassy and I just about crawled inside. Finally, I met Dr.Lichtenfeld. He was a kind German man, about 50, bald, had rounded features and wore glasses. He told me of the Greek hospital system: the prices were high for the private system, but there was a low per diem rate (about $15) for the state system.

“Unless you need a nurse, you are better off to stay at the Hilton for fifty to sixty dollars per day.”

I told him about my journey.

“You would make quite an endorsement for Honda,” he said.

I had torn a groin muscle, but it was not torn through.

“Pain is your friend, ” Dr. Lichtenfeld said as he prodded me, summoning my newfound companion. “It tells you what you can do and what you can’t.”

He gave me 20 – 222’s for the pain. He told me of his work with lepers, who had no nerves – they could feel no pain.

“Rats would eat their flesh when they slept…some would loose hands, feet, even legs.”

So I was lucky to have this new friend. But I was dismayed to learn that this friend would likely be around for a few months. I would see Dr. Lichtenfeld at the embassy when the friend seemed to get out of hand. He gave me injections for the road ahead including a large gamma globulin shot in the rear that made me dizzy. (This was for hepatitis and was good for six months). He told me how the body reacts to antibodies and how they can often do more harm than good. He gave me advice on travelling in the tropics. He gave me some diarrhea pills that he said were more effective than Pepto Bismol.

“The body takes of itself,” he said. Even with cholera, the body’s antibodies compete for the food that you eat. If the cholera wins, you’re in serious trouble. If your germs will out-eat the cholera, the cholera will starve and die. If you take antibiotics, they can destroy the cholera – or your own antibodies. But this is very rare.”

He was glad that I took the needle so well.

“I had a 300-pound RCMP officer who nearly fainted on me when I gave him a shot,” he said.

I moved around the embassy like a crippled old man. A girl named Ruby typed a letter of recommendation for me to take to the Egyptian embassy to help smooth my request for a visa. I learned that our Ambassador to Greece wanted to see me tomorrow.

At the entrance to the embassy, a guard wrote a note for me to give to a cabby to take me back to Camping Dafni. I struggled gamely to the corner but no taxi driver was willing to take me. At 3:00 p.m., the embassy closed and I saw Ruby walking toward the bus stop. She hailed a cab that took me to the bus depot. I didn’t have the right change for the bus. A friendly German man who was about to board took my 100-drachma note and stopped passengers before they boarded to make change for me.

It rained that night in camp. The next morning, I walked to the reception office. My leg felt better but not enough to risk venturing back into the city. I called and cancelled my appointment with the Ambassador. I needed to rest, to keep off my feet. I was given a new appointment with the Ambassador and they felt they could also take care of my municipal appointments as well.

It was just a well because it rained off and on all day. I packed up a parcel to go back to Canada. The manager, who I now called Bill, seemed anxious for me to leave, though he would always greet me, “How are you, my friend?” He said he had orders to close up the camp tomorrow. But the widow across from me said she was leaving soon but did not know when.

In pouring rain, I waited for buses to take me to a branch office of the OTE (the Hellenic Telecommunication Company) so I could make a phone call. Rain was forecast for the next several days – a great time to have to move, eh? I slept uneasily as it was difficult to roll over: my right leg felt like hammered lead. I was stiff in my left side and neck. I wrote notes in the tent in the light from two candles and used Melawend’s platform for a desk. I thanked God I was alive and could dream and work to make dreams come true – and I was thankful for all the help I had been getting with this dream. But I also wished that I had a 1987 Playboy desk calendar. That part of me felt just fine.

The next morning, I rode painfully into Athens. On the bus there were young guys in black leather jackets and girls in tight jeans and bright-colored sweaters. They had mostly dark hair, brown eyes and the clear olive-coloured complexions that was typical of Greeks. A few guys were clowning and some girls were giggling and I wished I’d had to nerve to talk with them. I looked out the rain-spattered windows. Under a lead sky, I saw men with moustaches and combed-back black hair. I saw salvage yards littered with wrought iron doors and gates, planks, thin bricks for walls, window frames, and signs in big squared Greek letters, painted mostly red on light backgrounds. In another yard, I saw rusting cars parked tightly together, looking like so many old people sitting grimly in an institution, waiting for someone to do something useful and fun with them.

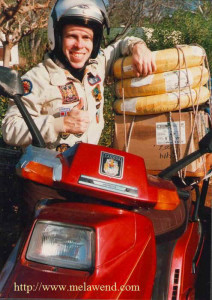

In Madrid, I had sent a letter home requesting that supplies, including spare tires and motorcycle parts, be sent to me in Athens. The supplies had not arrived. I made calls to Canada. They would be coming as soon as possible.

By the way he drove bus 880, on my return to Camping Dafni, I was sure that the driver’s dream was to race the first bus at the Indy 500.

My intentions in Athens were primarily to get out of it. I would take in the Parthenon, of course, but Athens was to be my springboard to the Middle East and to Africa. I had wanted to take a ferry to Israel and ride the east end of the Mediterranean to Egypt but I felt thwarted.

“If they see an Israeli entry stamp in your passport, they will not let you enter Egypt.”

That is what a traveler who had just come from Israel had told me. He was referring to Egyptian Customs at the border with Israel. This was not new to me. In Canada, it was suggested that I get two Canadian passports. After visiting Israel, I was to backtrack and use the other passport to enter Egypt from Greece. But I thought there must be a more legitimate way to do it. After all, I was on a mission of peace and did not want get myself arrested for any border-crossing shenanigans – not good for my diplomatic résumé, either.

But that was the paradox: the best place to promote peace was in a place of war, or to at least visit a war-torn area and report on it to others who enjoyed peace and perhaps took it for granted. I toyed with the idea of getting a second passport here in Athens, but my cautious side won out and I very reluctantly decided to give up going to Israel. I told myself, I will go to Israel, someday.

While I was dealing with this, I wandered the streets of Athens, looking for supplies. On Athinas Street were there were many small shops that were crammed with every imaginable bit of hardware, a lot of it carried out to the sidewalk in front and displayed so that you had one contiguous row of everything from air pumps to lawn rakes. I bought a bread knife. I also bought two crucifixes at a religious artifacts store, one to carry and one to put up in the tent. Since the accident in England, I had increasingly come to believe that Someone truly was with me. Melawend and I passed a small grocery store that had garlic hanging from string and pastry shops with clear plastic bags filled with baked goods.

I went to an OTE office and called Dad. As I was waiting for the call to be put through, I reviewed my mini-portfolio of 5-inch by 7-inch photographs. A pretty hazel-eyed Polish girl sitting next to me leaned over, with her face just inches from mine.

“Beautiful!” she said. “You give me one?”

I was saved when my name was called.

“How are you, son?”

It was great just to hear Dad’s voice.

I finally kept my appointment and met our Ambassador to Greece, Mr. Andrè Couvrette, a distinguished middle-aged man dressed in a gray three-piece suit. We shook hands and he signed the Odyssey Book. He was concerned about my travels through Sudan.

“Your only way through the South may be to fly from Khartoum to Nairobi.”

While I was at the embassy, I was given some reading material – a copy of the September 8th issue of Time. Perhaps it was just coincidence that its cover story was about Honda. I took it back to Camping Dafni, made a sandwich, and turned to the article. The more I read about Honda and the “Honda Way”, the more fascinated I became, and more intimidated.

Honda Motor Company, which Soichiro Honda started with 20 employees in 1948, was now the largest Japanese firm launched since the end of World War II. By 1960, it was the world’s leading motorcycle and motorscooter manufacturer – and it still retained that position. It was Japan’s biggest engine-maker. The company flourished in the 1970s when OPEC quadrupled the price of oil and the demand for small cars skyrocketed. Honda now had 58 assembly plants in 32 countries. The company had recently moved into its new 16-storey headquarters building across from Akasaka Palace in Tokyo. But the two top executives – Chairman Noboru Okamura and President Tadashi Kume, did not have the luxurious offices one might expect – they shared a “spacious carpeted room” with 31 other senior executives, with “not a partition in sight.” All 1,300 employees at Honda HQ shared the same cafeteria – there were no executive dining rooms. It was a company that did not seem to recognize individualism. I remembered learning in school that conformity was the general rule in Japan. So I wondered, Why would they even want to meet someone like me?

But apparently Honda differed from other Japanese companies by its openness. At its headquarters – where I planned to go – it had a glitzy showcase lobby (what I would discover as their “Welcome Plaza”). Visitors off the street could come in and paw new cars and motorcycles in an entertaining and informative atmosphere that included a 12-panel movie screen. Even from the top, it seemed Honda did have a desire to reach out and welcome its customers. (Perhaps even a scooter-riding ambassador in blue jeans?)

In a tent on a terrace above me, there was a young couple from Melbourne, Australia. She was about 5’1″, and had long blonde hair, blue eyes, and a smooth tanned complexion. She had a nice smile and a soft voice (I could hear the couple talking but was not so close that I could understand what they said). I met them later. They had been travelling in Europe for two years and had worked briefly in England. They had saved for this trip and were living on the cheap. They planned to be back in Australia in about a year, after going to Egypt and India. These were the first of many Aussies that I would meet who would tell me about long-term trips they were taking.

“It’s really expected that you will lash out at least once for a year and travel,” a girl from Sydney would tell me. “It’s because we are so removed from the rest of the world that it is so expensive to travel outside of Asia.”

I called Iphigenia, a penfriend of three years. She too had a nice energetic voice. Indeed, I learned that she had married and become pregnant since my last letter several months ago! She told me that she was lying down all the time. She had been staying with her aunt for the last two and a half months, and would be until she had the baby. She told me of the time she and her husband went picnicking in the mountains and their car broke down.

When I went over to her aunt’s apartment and met her, she was lying on a couch. Work had taken her husband away briefly to another city in Greece. Her graying aunt served us dinner of peas, beans, white cream cheese, boiled egg, sardines, white wine and cookies and Greek tea. I ate while she talked. She reminded me of a girl who, as soon as she learned she was pregnant, took to her couch and expected to be waited on hand and foot for the duration.

It was late in the afternoon when I got on a bus to and headed back to camp. About half way through the city, the bus was stopped by a group of shouting protesters who were tying up traffic with their march. I jumped out and tried to record them but realized later that the pause button had been on. (I had not learned my lesson from the cookoo clocks in the Black Forest!). A young guy in the noisy crowd said that the protest was about the government closing up a factory.

I was standing in front of a small cinema and on impulse, I decided to go in – I just wanted to see a movie, any movie. I did not even look at a movie poster, marquee or studio card. A man in line said he was a seaman and had been to Canada. A 60ish witchy-looking woman was in the ticket booth. After I paid her the 250 drachmas for admission, she said, “Present, please.” I didn’t know what the hell she meant. I gave her 20 drachmas more and that seemed to satisfy her. I went into one of the small theatres where the floor swooped down under the few rows of seats and up to the small screen. I was in the company of perhaps 50 men of various ages. Some men wore business suits but most of the audience looked like sailors who were on leave. They were wearing battered jackets and dull rumpled clothes.

I had not known what kind of theatre this was.

*****************

WARNING TO PARENTS AND MINORS:

The following paragraphs are sexually explicit.

On the screen there was a tall, dark-haired stud with an extraordinarily long dick and he was busy putting it into several women. In once scene, he was with three beautiful girls. He had them go on their hands and knees by a fireplace and show their asses to him (even Shakespeare used the word “arse” in Romeo and Juliet). He chose a busty shorthaired Caucasian girl and entered her from behind. He took a Negro girl missionary style, and then the third girl sat on top of him. In another scene, a woman was smiling as her face was torpedoed with semen. There were numerous scenes of women performing oral sex on him, and he on them, and close-ups of him penetrating women. When one woman was nearing climax, he rolled her onto her side, thrust his himself into her and pumped like a revved-up internal combustion engine. It was as intimidating as it was titillating.

There was no plot and not much variation except that you sometimes saw women doing each other, or alone, using dildos. Mostly it was very graphic pumping, licking and sucking. No condom was used. There were Greek subtitles to dialogue that I also did not understand, but who cared? My fellow patrons were silent and rather stern-faced and kept their eyes glued to the screen.

I left the theatre feeling that I had, to some extent, comprmised my own morality. But I also took from it something good – in the sense of one man and one woman in an exclusive and enduring passionate relationship – a reminder of what I was missing, and looking for.

(Okay, back to PG rating…)

*****************

Back in Camp, virtually everyone had left. A couple across from me was setting up a tent by car lights. It was cold in camp. You heard the echoes of dogs barking. One of the three stray dogs involved in the accident walked slowly up the lane with its head hung down almost to the ground. I patted the dog and it responded by relaxing. It seemed that dogs got lonely too. Bill had said it was common for pets to be abandoned.

Maria Economou was diligent in trying to arrange meetings for me with someone at City Hall. She got me through to the secretary to the mayor. This was an awkward time to see the mayor of Athens in part because he had been defeated in a recent election. The new one was not to assume power for two months. I was sent over to the headquarters Greek National Tourist Organization (GNTO) and met the Director. He was a stoical man seemed puzzled by my presence.

“Cannot our regional office in your area handle your request?”

I did not feel optimistic about asking for any form of sponsorship here. I was told that their director in Toronto would be notified of my request for information. The concept of an information exchange was lost here. Someone suggested that I be included in upcoming “familiarization tours” of the kind that are provided to travel agents.

At City Hall, the mayor’s assistant accepted my papers.

When I left City Hall, it was raining. I stopped at an OTE branch on the way back from Athens and learned from Mike Carroll at Peace Bridge Brokerage that the shipment had not been sent out – the motorcycle parts I had ordered by phone from Madrid six weeks earlier had not come in. But I did get good news from Lynda Sykes, Manager of Tourism for the Greater Fort Erie Chamber of Commerce.

“We have received tons of materials from the UK, and Scandinavia…you should see the posters from Switzerland!” she said. “The shipment from Cannes came first-class.”

Lynda was enjoying the packing up of materials about our area and sending them off to those places.

I was still having difficulty walking but my groin was on the mend. I was, as Hemingway put it, “happy in feeling the pain lessen.” I felt that my “friend” had already overstayed his welcome.

(This was something I was to learn about myself as someone’s new friend. It would become particularly evident with future American hosts when I would feel estrangement from having stayed with them too long. I guess I became something of a pain to them, as you will see…)

I learned that the Adriatica Line had a ferry that sailed to Egypt every ten days. I had time to make arrangements: get my visa, get $300 together, get supplies, request my shipment be forwarded to Cairo, get film ($20 per roll). The biggest challenge is that I would have to try to get a pass from Adriatica, worth about $180. ($140 for me and $40 for Melawend.)

I looked at my map of the world and realized just how much world there was ahead of me. I had zigzagged through Britain, Scandinavia and Europe. I estimated that if that line were straightened, I would have covered the distance from London to Beijing – but I was still in Europe.

I needed more time to heal. I felt now that Jimmy Bedford was right when he had suggested that it might take me a bit longer to get back than expected. So I set my sights on returning in the autumn of 1987. Besides, I was enjoying all this diplomacy and article writing and the taking of photographs. I was even getting out of my shell and meeting people. I was in no hurry to get back.

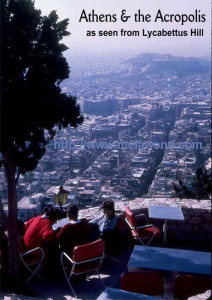

And I wasn’t helping the healing matters any either. I hated being restricted in my movements so I did my best to evade my friend, or at least ignore him. On one trek, I walked up the many wide steps to the summit of Lycabettus Hill and took in my first view of the Acropolis and of the congested city that sprawled around its base. I took these photos from the white Byzantine church on the summit – St. Georgios. But I would pay for these excursions with intense nightly visits from my friend.

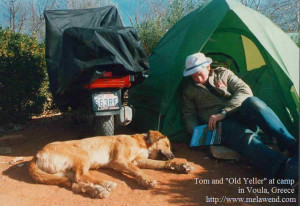

Bill was curiously absent when I packed up on November 7th and moved out of Camping Dafni. I rode out to Voula, on the southeast outskirts of Athens, and found Camping Voulas on the coast. My GNTO guide said that it had room for 297 people in 99 sites (43 tents, 56 caravans) and it was open all year.

Great!

The place was nearly deserted. It was flat with small leafy trees. I chose a site near the washrooms. Many sites had a leafy hedge for a border and enough room for a tent and a small car or a scooter. About five sites away, my nearest neighbour was a 40ish, short, busty, big-assed German woman who wore sweat pants, a sweatshirt and a bonnet. She was always jabbering to herself and to anyone who crossed her path. She had a small tent at the corner of the lane and it looked like she had been there for some time, alone. Rocks and branches wer piled around the edges of her tent as if to hold it down.

I soon discovered that the camp was near the flight paths of Athens International Airport. I thought, Oh well, I won’t be here long anyway.

(Wrong!)

I settled in. The next morning, I finally did some laundry, using the camp’s washing machine. There was a couple from Windsor, Ontario nearby and they were listening to Casey Kasem’s Top 40 Countdown on a radio. When I heard this, I felt that I was still very much in the Western world. It was comforting, but also frustrating because I was supposed to be on a journey around the world.

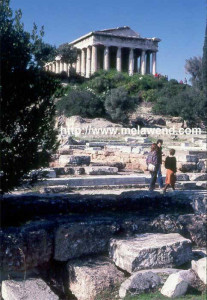

To cheer myself up, I took the bus into Athens and walked to the Plaka. This was the old town in the shadow of the Acropolis – narrow streets and alleys, neoclassical villas, taverns and cafeterias and the ubiquitous tourist shops. Adjacent to the Plaka, I wandered around Monistiraki – the traditional flea market area. Beneath the ponderous honey-colored ruins atop the decapitated hill that was the Acropolis, I poked around the kiosks looking at plates, necklaces, decorative pieces made of hammered copper, fans and furs, all the likes of which I had not seen outside ethnic shops in Canada. My ears picked up a souvenir I could afford. Beside one of the kiosks, I sat with my cassette recorder running inside my daypack and recorded some great rebétika music. This was the tinkling combination of Greek and Byzantine traditions flavoured with influences of the East and featuring the bouzouki, the long-necked, pear-shaped guitar-like lute.

At last, this is Athens, I thought, this is Greece.

At the office of the Adriatica line, I learned that there was a ferry leaving for Egypt the same day; the next one would leave in 10 days. I went to the embassy. Maria was just getting busy with her consular work, visas, and passports. I felt like an imposition, as there were many people there to see her. I went to the GNTO and saw Lisa Greenberg to ask about camping at Camping Voulas. She made calls. I got sponsorship to camp there for 10 days. I had a place to stay and plenty of time to arrange for transport to Africa. I had some time to invest.

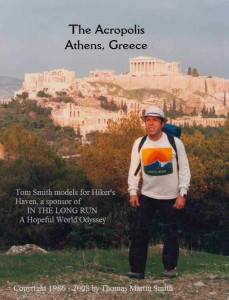

So many travel writers these days are anxious to take you “off the beaten path” and avoid, like the proverbial plague, even a glimpse of what is considered a cliché. But if their vision, as well as their subject, was truly unique, I reasoned, were they then not depriving you of something? Was it simpler to write about the uncommon as opposed to the cliché? And, as with the Eiffel Tower in Paris, how could you go to Greece and not see, at least once, the Acropolis? There was no thought of cliché in my mind.

Mark Twain had been so enraptured by thoughts of seeing the Acropolis – and so angered by the quarantine that threatened to prevent him from doing so, that he and a few of his fellow innocents aboard the Quaker City jumped ship one night. Under clouded moonlight, they “toiled laboriously” over stony hills, pilfered grapes in vineyards on their way, hurried across a ravine and up a winding road “under the prodigious walls of the citadel” to a wooden gate that was locked. Bribery got them past the guards.

Well, I didn’t have to sneak up to it but I had to resort to skullduggery of a sort. There still was a wooden gate and there was a guard. I was nearly broke (I was always nearly broke). I showed him Lisa’s card and he admitted me for student rate. I scrambled up the remains of the Propylaea, and onto the summit of this massive hewn limestone hill. And there they were, in all their foretold honey-colored ruined grandeur: the temple to the goddess Athena Nike, the Erechtheum and the quintessence of Greece, the Parthenon.

The place was a mess! To borrow a line from Timon in Walt Disney’s The Lion King, “Talk about your fixer-upper!”

But of course they were crumbling! This decrepitude was wrought by centuries of fire, vandalism, religious intolerance, gunpowder explosions, pollution… The Acropolis looked like a monumental metaphor for the human condition – tremendous potential undermined by tremendous abuse and neglect.

I was not a passionate lover of ruins but seeing the sad state of these once majestic buildings and statuary that towered over the land, well, it was enough to make me weep, if only inside. But efforts to restore the place were being made. Athena Nike’s poor old temple was encased in scaffolding. Manolis Korres, chief restoration architect, was three years into an effort to save the Parthenon. There was more scaffolding but it was inside that building. It was still impressive, and brought to my mind the attempts by latter-day architects of courthouses to imitate the Parthenon’s columned, gabled glory. And as at many restoration sites, the botched attempts of previous restorers would have to be dealt with here. The iron supports that had been cemented into the marble by Balanos in the late 19th century were rusting. Korres and his crew would painstakingly remove the concrete and iron and replace them with marble from Mount Penteli, where the original stone for the Parthenon had been quarried.

I scrambled up to the Parthenon over a slight but torturous slope of white rock that looked like the sun-bleached remains of an ancient volcanic shore. I rambled all over the stony grounds, dodging fallen bits of temple here and there. I observed tourists. I stood by a low stone wall at the edge of the Acropolis and looked out over the sprawling mass of low, ivory-colored buildings that comprised Athens. Stark in the distance was Lycabettus Hill, looking like a mammoth breast sheathed in green with up to a huge bared nipple that had a drop of white milk seeping from it (this was white-walled St. Georgios Chapel from where I had taken telephoto shots of the Acropolis). I stepped back to capture in the foreground a young couple that was looking out over this scene.

Click.

Again, I felt the longing to share this with Her. (Yes, I know that you are not surprised, but please bear with me.) The Acropolis and Athens were places to be shared with someone you loved.

I did my photographic thing for Hiker’s Haven, and my journey, using myself as the model and the Parthenon for a backdrop. Some tourists looked at me like I was a bit odd as I changed into a sweatshirt with a bright-colored logo and then into an even more colourful Odyssey Jacket that had many national crests, taking pictures of myself with the aid of my friends – my Minolta X-700 cameras and my three-legged companion, the Manfrotto tripod. I didn’t care what anyone thought of what I was doing.

I finished, then parked my rump on the steps of the Parthenon where I imagined millions of other rumps had been before mine. I watched the ebb and flow of tourists. I thought of how such places as this were valuable if only to remind us of our potential for architectural expression and achievement. Here I was, sitting on the steps of the Golden Age of Greece, touching the genius of Phidias who worked under one of the country’s greatest-ever leaders, Pericles. It was extremely humbling to think of such accomplished men, measuring their achievements against those of an odd lonely fellow who had been taking photographs of theirs. Like this temple, I too had been in decline – restoration all around was in order.

I stayed long enough to see the setting sun turn the buildings of Athens a mellow shade of coral. Then I headed back to camp.

(I had anticipated being in Athens for about 10 days or so. I would be stuck here for 58. Things had a habit of getting in the way…)

My top priority now in Athens was to secure onward passage to Africa. To do this I had to go the office of Adriatica di Navigazone in Piraeus. Here I met a Massimo Lanzetta, a happy man who enthusiastically supported my journey and sent out a dispatch to Venice. Within a few days, I had my pass for the 36-hour voyage to Alexandria. People like Massimo and companies like Adriatica were as blessings upon my odyssey.

The ferry was to leave the next day (November 20). I beat a hasty retreat to Voulas to pack up, stopping to call home to get the shipment rerouted to Egypt. I took those long last looks at a place you have gotten use to. In the morning, I scurried back to Piraeus, stopping long enough to buy a new brake handle for Melawend. I was ready for Africa! But when I got to Piraeus, I learned that a strike in Venice had delayed the ship for two days.

Back we went to Camping Voulas.

“You are back again?” the camp registrar said.

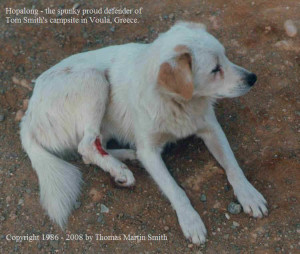

Finally came what I thought was The Big Day. When I awoke it was cold and the sun just was starting to rise. I was later told by a storeowner in Glyfada who said his brother in Montreal told him that they were already shoveling snow. I divvied up the rest of my bread with the stray dogs, several of which were pregnant. Small birds that looked like finches joined the dogs. Three dogs came over while I was packing up this morning and hung around. One was a meek black dog, with brown around the eyes. I gave him some bread. He took it away to eat and a vicious little white dog came and tried to take it from him. I chased him away. (I would later grow fond of this feisty little dog.) The third dog was a mongrel with a lot of Irish setter in him. He looked like Walt Disney’s “Old Yeller”, but with sleepy eyes. He took one of my ropes away, played with it, and would not give it back. I stepped on it and took it back. Seeing there was no more food to be had, the dogs left. I finished my packing, took one look around and sped to Piraeus.

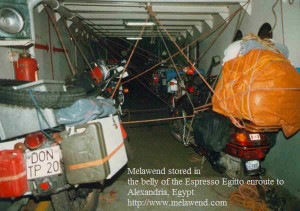

I got my visa, got my passport stamped by the police, and passed through the formalities in the dirty, dimly lit Customs office. I had, in effect left Greece and was now in the parking area by the berth of the Espresso Egitto, which was just now backing into it, belching a plume of thick velvety black smoke.

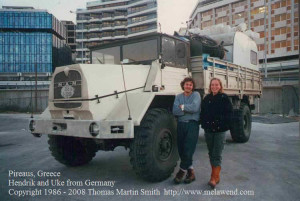

Melawend and I waited to board and we had lots of company. There was a row of heavily loaded Land Rovers and crews in dull, durable clothing. I waited with others who were sitting on motorcycles. These included a British couple on big BMW 800cc painted in Zebra stripes. The guy was tall and looked too young to have grey in his curly black hair. His girlfriend had dark brown hair, wore sunglasses and sounded American. There was a short, lean, blond-haired German carpenter next to me who was also riding a big old BMW 800cc with an eye painted on the gas tank. He was going to South Africa where he hoped to work for awhile. When you said something that made him smile, his eyes would squint. There was a big bearded Austrian who looked like Kenny Rogers when he was with The First Edition. He had a modified BMW that looked like something out of a Mad Max movie. It had a huge racks welded to the rear of the frame that carried two aluminum cases and three military gas containers on top. He sat astride a huge, custom-made gas tank. All these riders had provided for extra gas capacity and had surprisingly little packed gear. These people were veteran travelers.

(I made mental notes of what I saw and heard but I would not put them down on paper until I was back on the beach at Camping Voulas that afternoon. Yes, Camping Voulas. On the beach, I paused to watch a couple walk by: a guy walking at a brisk pace; a girl in tight red sweat pants jogging. She had a big ass. Quite a few people were wearing bathing suits. Some people were swimming. I heard lawn mowers in background. I kept to myself because my heart was in my throat. I kept writing…)

It had taken a long time for the people that had just arrived on the Espresso Egitto to disembark. Finally, the ticket manager from Adriatica came over. He went around to each of the owners of the cars and the motorcycles and each produced an orange booklet called carnet. He came to me.

“No carnet?’ he said. “Impossible to enter Egypt without carnet.”

I felt suddenly sick. Several of my comrades-in-wheels came over and expressed surprise that I did not know about a carnet. Basically, it was a bonded passport for the vehicle that had to be inspected and stamped when you took a vehicle in and out of a country. Your auto club issued it. You put up money, in my case about twice Melawend’s value. Were you to sell the vehicle while in the country, the Customs of that country could claim the duty that would have been payable for import – as much as 200% duty in some countries. But a carnet had not been mentioned to me when I visited the Egyptian travel agency in Athens. I was told that you were supposed to get some kind of green card within seven days of entering Egypt (they too probably assumed I knew about a carnet). The riders just laughed when I asked about insurance.

Of course I had heard about a carnet back at Gatwick, but as you recall, the two senior Customs officers exempted Melawend with just an explanation – I had not thought about a carnet since. But that’s just a lame excuse for not having asked enough questions before I left home.

My comrades-in-wheels huddled around me thinking of options for me. I felt I was holding them back.

“Maybe you can go via Turkey,” said the Austrian.

“No, he’ll need a carnet for Turkey for sure,” said the guy from England.

“This is a shitty situation for you,” said his girlfriend.

“You can try to enter (Egypt) illegally,” said the German carpenter with a squinty grin. “Then you forget it (the carnet).”

“Fuck!” This was an echoed sentiment.

I considered my plight. The next ship was in eight days. I considered trying to get a two-way ticket, get to Customs in Egypt and explain, and have recourse if I was refused entry. I could board now and try my luck… I had five minutes to make a decision.

On the road back to Voula, I was torn:

I should have tried to go, damn it!

I started to look for a gold lining – all the things I could do to better prepare myself.

I can rest up because my groin is still bad…

Oh God, not that squawking German frump again! And those damned jets! (Over a million people flew into Athens airport each year.)

What to do? .

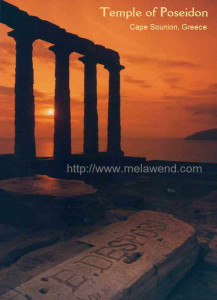

I must reroute the shipment back here. I can go the National Museum – it has the best archaeological exhibit in Greece. I can send mail more safely here – I’ll send some extra gear home. I can go to Sounion and meet Byron. I can see Tatiana again!

(I’ll introduce you to her shortly.)

I was just trying to cheer myself up. I throttled up for Camping Voulas.

“You are staying again?” the registrar at the camp said.

I went to the beach and began writing down all the things that had just happened. I caught up with myself when I wrote: “The girl with big ass stripped off the red pants and went for a swim. Now she’s running again, I watch her ass bounce. I watch near-naked girls swimming. If I had to have a setback, what nicer place than to wait it out here…”

I was trying to cheer myself up by distracting my thoughts. Getting horny was a most effective distraction.

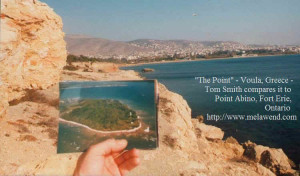

But what had I to bitch about? Life was good at Camping Voulas. When I set up my camp, again, I walked out for the first time to a low scrubby headland that I would call “the Point”. Simply by its location at the west end of the bay at Voulas, it reminded me of Point Abino, a much-loved place back home that was like a sanctuary to me. From this Point, I could look across the sweep of the bay to a disco on the far side that took the place of the Comet rollercoaster in Crystal Beach.

There were actually two points here, separated by a small cove that was favoured by fishermen. On the clearest days, you could see Lycabettus Hill from the Point. You could see Piraeus and the many ships around it. There were small islands off shore.

On the tip of the main point there were the remains of gun emplacements with narrow concrete steps leading down to small octagonal concrete enclosures beneath circular rims that held the guns at ground level. I thought of how Rob and Stuart Hadden, Bobby Adams and I would have loved this deserted place for our war games. There was rusting barbed wire meshed in with the thick low carpeting of plants that had rubbery stocks and was full red blooms.

The water here was deeper, in shades of blue and green. On my treks to the Point I would pick up artifacts of life along the beach – hair combs, hairpins, shells, a baby’s pacifier. I would walk along the beach to the paths in the red earth and come out to the Point to write, to look at the Mediterranean, to see the Olympic Airways jets come in. But mostly I came out here just to be alone and to think. And out here, I would fantasize about being in such a place as this with Barbra Streisand, talking with her about world peace.

(I admired Barbra for all the well-known reasons – her awesome voice and her acting and comedic talent, and her beauty. I also admired her because she was such a multi-talented girl. She pursued her goals with great tenacity, reason and passion. She was emerging as a powerful and passionate voice in political and environmental activism. And I believed that we would be in sync in believing that the essence of world peace was about people needing people.)

Out here, by the sea and the seagulls, I could nurture my dreams and ideas and be Jonathan Livingston Seagull: “…hungry, happy, learning.” I hated to leave the Point when the rudeness of reality interrupted my daydreaming: I’ve got to go and take care of that.

I walked over to what appeared to be an abandoned house near the Point. Then I heard live piano music coming from it. A man came to the upper window.

“Where do you think you are going?” he said.

Massimo Lanzetta’s face turned white when I walked back into the Adriatica office, but he laughed it off and issued a new ticket for me. A telex was sent to our outpost in Cairo to say that I had been delayed. I was to leave a week from Sunday.

This too was not to be.

At the OTE office in Glyfada, it took 4 hours to make the phone connection with Mike at Peace Bridge Brokerage. The shipment still had not gone out – the parts had still not come to Lapp’s shop! I approached the Egyptian Embassy about my plight and a telex was sent to Cairo to see about an exemption for the carnet (though I had a gut feeling that I would get flat-out refusal in all third-world countries). I assumed all of this could be done within a week.

(Lesson learned about travel: NEVER make assumptions – check it out, thoroughly.)

Two days later, I was informed by the Egyptian Embassy that not even an Egyptian would be granted exemption. (Of course not – an Egyptian would be importing the vehicle to his home country! I would certainly just be passing through – unless I met and married and Egyptian girl.) I began to feel that if I could not get Melawend into Egypt, Cycle for Life – World Odyssey was dying.