Chapter 24: The Ups and Downs of Egypt

PART V

Shades of Africa

Chapter 24

The Ups and Downs of Egypt

“…into that old land that knew all which we know now, perchance, and more…”

Mark Twain The Innocents Abroad

Into that old land came Mark Twain and the “innocents” aboard the steamer Quaker City in 1867. And at the end of 1986, the innocents were still coming, including me.

Ah, innocence is bliss!

Well, something like that. But innocence could be just a euphemism for ignorance, an excuse for arrogance, or a cover-up for stupidity. I knew very little about Egypt except that it had a lot of crumbling sand-swept ruins and that it was all searing desert except for the Nile, which cut a green-fringed swath through it. Arabs lived there and they were all – remember how I described them way back in Canada? – “shifty-eyed, balloon-lipped, bearded thieves and assassins who would slit your throat on a whim and shout, ‘Allah!’” And so I dreaded even the thought of entering Egypt. But what did I know about Egypt or Arabs?

(And why did the those images, mostly from stupid old cartoons, stick in mind?)

Right up until it was destroyed by earthquakes in the 12th and 14th centuries, my first sight of Africa, in the direction I was currently going, would have been one of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World – a lighthouse that towered 440 feet (134 meters) above the Mediterranean – the Pharos of Alexandria. In reality, my first sight looked like a scene out of a spooky cartoon, and we were cruising into it. First there were a few rusty cargo ships, then a sea of them. There were modern container ships in this sluggish flotilla, but most of the ships were aging derelicts, many of which seemed to be running too deep in the water. Seeing this from the high clean decks of the Espresso Egitto, I felt as if we were on a regal ocean liner, one that was headed into a neglectful senior citizens complex for mortally afflicted ships.

And there, behind it all, was Africa. Or was it? It was flat. The shore looked like a massive interconnected fleet and these relics were pieces of flotsam bobbing around it. Of course it was not that simplistic nor should I have been surprised. I guess I had let grandiose images of “The Dark Continent” build up the illusion that you would approach a towering, intimidating shore that would bear down on you: This is AFRICA! Beware those who enter here!

I was nervous but this was exaggerated by some Ouzo I had bought in Crete. In traveling to a new land, you felt you stepped timidly onto one edge of it, found and became familiar with solid ground, then traveled across it and came to another precipice. Then you wanted to hold on to the now familiar land for reassurance before stepping carefully over into the next.

But if I was a latter-day Odysseus, where was my Athena?

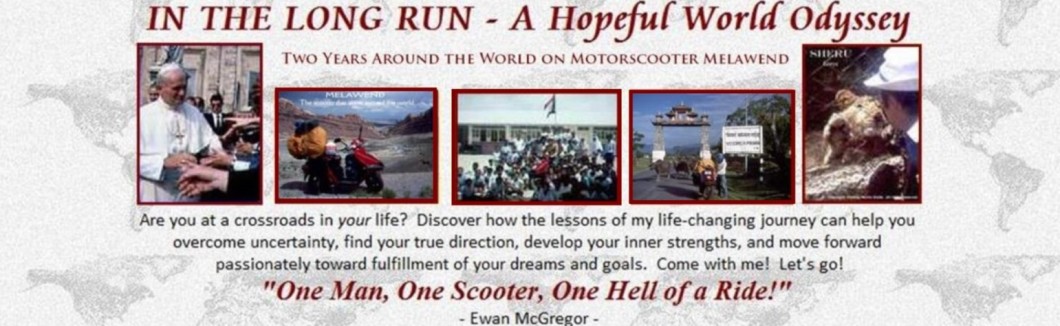

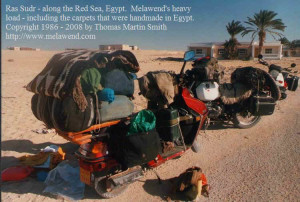

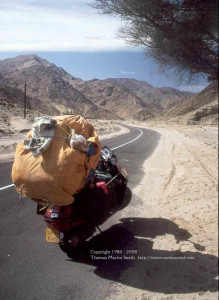

Before we could dock, four Customs men in military uniforms boarded the Egitto. They commandeered a large room where passengers had to submit their passports and exchange hard currency for Egyptian pounds. You began handing over extra money with no idea of what you were paying for. These were men of few words and even less patience. A tall muscular man went with vehicle owners down into the dark hold. He clambered over the MAN army truck, a German-licensed Winnebago and the Land Rovers. He poked around the motorcycles with a flashlight. He was looking to match serial numbers on vehicles with those on the carnets. For Melawend, he was satisfied to see that she looked like the same heavy-laden scooter he saw in my photocopied news articles. (He was getting annoyed that I did not know where the serial number was, and I didn’t want him stripping her down to find out.) This was the easy part of entering Egypt.

I could write for you a chapter on the labyrinthine bureaucracy I had to go through to clear Melawend – all the shuttling back and for the between blue-painted sheds, handing over my documents (worried that I would not get them back), handing over money (knowing I would not get any back), getting stamps, getting a crude license plate that was hand-painted in red letters on a yellow background.

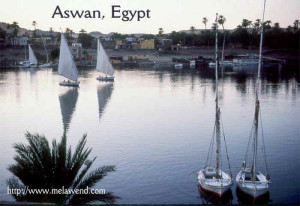

(In Aswan, it was demanded that I surrender two plates – but we’ll get to that bit of nonsense later.)

There were so many “officials” to see here. All of them scribbled something down of some pieces of paper and would send me on to another official. I wondered if this was the Egyptian way of creating jobs. It might have explained why there were so many fees to pay.

As we began the ride out of Customs, all the motorcyclists were directed to a park by a low outside wall were we were lined up for yet another inspection. This time, I submitted to unraveling Melawend’s humungus load when an inflexible official said, “Open.” After two more forms and some incoherent grumbling later, he said, “Finished.”

I simply left when I was done and rode out into the city that was founded over 2,300 years earlier by the Macedonian king, Alexander the Great. Now we entered the unfamiliar chaos of the streets of Alexandria. Since I had Canadian stickers on Melawend, the first non-official words I heard from an Egyptian came from a taxi-driver who ignored honking horns to say, “Canada! Number One!”

(I would test this apparent bias in Cairo.).

Amid the many scarred utilitarian-looking scooters that filled the streets, Melawend stood out. With her sleek maroon faring and big Cycloptic headlamp, she did look like something out Star Wars. This made me nervous. I bore in mind the Arab proverb: “Trust in Allah, but tie your camel.” I promised Melawend that I would stick by her at all possible times.

At first, I was intimidated by all this unforeseen attention. But the people were so friendly. Everywhere, they gawked at us but did so with smiles on their faces. At one corner, Melawend attracted a crowd of boys and old men who, as one, were excited to give me directions. At another intersection, an Egyptian executive in a western business suit pointed the way to the road that would take me across the desert. He said that it was four lanes and was very good to drive. I had not seen even one “shifty-eyed, balloon-lipped…” well, never mind that rubbish. My heart warmed to Egyptians as Melawend and I scooted out of Alexandria.

(Dear reader: we will be back to Alexandria much later, unexpectedly, so I’ll describe more of this fantastic city then. In the meantime, hold on! We are in for a bizarre time in the land of the Pharaohs!)

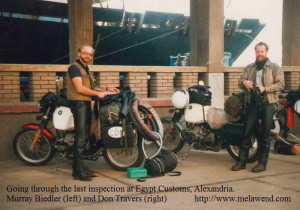

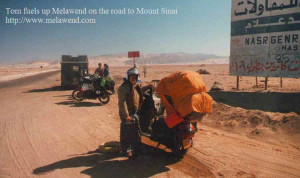

You left the city abruptly and found yourself in the green marshy lands of the Nile delta. The lush fertile land gave way to thinning stands of palm trees and pine trees that had long feathery needles. I was waved through a toll both for free by two young guys who smiled at Melawend and her huge orange-covered load. Trees soon gave way to flat scrubby grasslands that reminded me of eastern Alberta. In turn, this yielded to barren sand as the Desert Road left the delta, lived up to its name, and headed straight for Cairo. It was as good a highway as the executive had said.

As the miles drifted by, it suddenly occurred to me that I was beginning my ride across the mighty Sahara – the largest desert in the world. It stretched west to east for 3,000 miles, from the Atlantic Ocean to the Red Sea. It was bleak and empty, except for the incongruous strips of this divided highway and the truck drivers on them who always honked and waved.

It was hard to believe that the Sahara had looked like the savannas of sub-Saharan East Africa did today – a lush green area filled with rivers and wildlife. This was revealed in part through engravings and paintings left by Saharan hunter-gatherers about 8,000 years ago. Dinosaurs had also thrived in the Sahara region. All that had turned to dust and had blown away or was buried under these sands. The emptiness was so complete that there came a surreal feeling of riding through a void between worlds, like we might well have been on a Star Wars set.

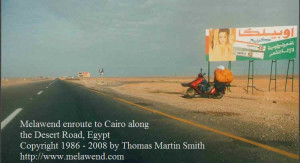

What also surprised me was that the air was so mild. I expected to be riding under blistering sun, to be gasping with thirst. But this was winter, December 31st to be precise. Melawend had the only thirst – for gas. And where to find gas in all this unending emptiness? About halfway to Cairo, I found an oasis.

This was Omar’s Oasis. It was a long tin-roofed restaurant that had tables and umbrellas outside. They didn’t have gas here. A young guy in a spotless white shirt and black bow tie held up five fingers and pointed further down the road. I asked about camping around here. He went up to a 55ish man who was eating at one of the tables under and umbrella and I saw him nodding. I got gas and returned. All I wanted was to camp in the desert nearby, but one of the waiters showed me to a concrete addition that was under construction and helped me get Melawend onto her centre stand.

“You come eat. No pay.” he said. “Don’t worry. Your things will be safe here.”

It was late afternoon. I had not eaten since the morning and the quagmire of Customs and the long empty road had given me quite an appetite. I was seated in the restaurant. There were just a few other customers.. It was a spacious low room of white stucco, lined surprisingly with knotty pine. The place was decorated with green, red and blue foil and Christmas hangings. Easy-listening western music played softly in the background. I had spaghetti and a Sport cola (made by Canada Dry) and four fresh dinner rolls. With my stomach full and my wallet spared, I returned to Melawend.

“Shukran,” I said in gratitude as I passed the rotund owner who was sitting with friends at table outside. He smiled and waved.

I didn’t bother to unload Melawend. I rested beside her on my sleeping bag, which I spread over a piece of hardboard on the concrete floor. I looked out through scaffolding to the darkening sky, feeling so lucky to be in Africa at last. I also became a bit apprehensive that scorpions might be lurking about. After nightfall, I began to feel loneliness creeping in. This was New Year’s Eve. Around 11:30, the music inside stopped and I heard laughter. I decided to go in and bring in the New Year with a cup of tea.

The owner and some businessmen were seated at a table in a corner. On one of the pine walls, a cloth bearing “1987” had been hung. Balloons hung from the ceiling and pillars. Two men at a table by the front windows were the only other guests. There were more waiters and cooks than there were guests and they would congregate at the open counter that separated the kitchen from the dining room. There was much laughter from the owner’s table. The men arose, shook hands with the owner and left. The owner walked by me, smiled and said something to a waiter who abruptly took away my tea. I was brought a big meal and a red candle. I dined on two salads, Kofta (a plate of five rolls of rolled breaded beef with a garnish of greens), and a plate of macarona bashmil (tubular macaroni and beef peppered with a brown-coloured spice). I was given a large bottle of Stella (a native beer) to wash it down.

Near midnight, the waiters lit candles throughout the room. Lights were turned off. The music was turned up – an instrumental version of “Evita”. There was no marking of the actual passing of the year. At 12:05, the lights came back on and waiters wished me a Happy New Year. I retired feasted and very happy. I thought of New Year’s resolutions – all the swearing off of transgressions after you’ve had the pleasure of committing them. My main resolution was to do the best possible job with my international project.

I was given the same hospitality at breakfast the next morning.

“No money,” the waiter said.

In the washroom, a man reached under the door of my stall to hand me some toilet paper. I saw this man later and he had eyes that were so crossed, you could hardly see the irises – I was reminded of the actor, Jack Elam. As I left, there were lots expressions of “Welcome!” “Happy New Year!” and doubled-handed handshakes. As I drove off, a waiter jumped to attention and saluted.

Such as these are the Arabs I had dreaded meeting? Aside from some of the bureaucrats, the Egyptians that I had met so far had been among the friendliest people I had met yet on the journey.

Unfortunately, I had regarded Muslim society as primarily mean and closed-minded. Egypt was 90 percent Muslim. Muslims followed the religion of Islam and the teachings of the Koran which all seemed to me to be a rigid, totalitarian way of living. And they had “fundamentalists” that were intolerant of anything non-Islamic and were extremely violent in enforcing their beliefs. Add to this that I believed that an underlying mission of most religions was to convert everyone else to their beliefs – in other words, to take over the world, religiously speaking. But what did I know about Islam, or about any of the world’s religions?

(Through confrontation and through friendly instruction, I would learn more about Arabs and Islam further down the road. For now, here is brief introduction… Islam comes from the Arabic root salima, to be safe: aslama, to surrender. Peace means “submission”, whether it be to God or fate, or to the social system framed by the Koran. The Koran, or Qur’an, literally means a “recitation” – the word of God in Arabic as directly transmitted through the Prophet Muhammad. It was laid down 1300 years ago in powerful prose combined with forceful rhetoric and rhythmic cadences. Egyptian tastes, habits, and preferences are referred directly back to the Koran. In addition to the revelations, a collection of sayings and actions attributed to Muhammad was compiled and committed to writing – the Hadith (traditions). Together, the Koran and the Hadith guide all Muslim religious and personal life.)

Perhaps because Egyptians had lived for so long under self-concerned and abusive conquerors, they clung to their best times – under Mohammed and his successors, the four Rightly Guided Caliphs, who brought justice, prosperity, and true belief to the land.

I was guzzling formula in my crib when the Republic of Egypt was born in 1953. From high-school days, I remembered only the glories of the pharaohs, and the Exodus. Much of my impression of Egypt had come from those old cartoons I mentioned, from vague memories of high-school history classes and epic movies, including Cecil B. DeMille’s The Ten Commandments. I understood that life had not changed much for the fellahin (native peasants or laborers) in thousands of years.

I had not appreciated that this was a country that had been occupied by invaders since the time of the Pharaohs. It had been a conquered nation when Christ walked the earth. In fact, since the Pharaohs had been defeated by the Persians in 332 B.C., until the revolution in 1952, Egypt had been under foreign domination – Persian, Greek, Roman, Arab, a brief venture by 29-year-old Napoleon, Turkish, and, the last to go, the British.

For the 72 years prior to 1952, Egypt had been under puppet monarchs manipulated by the self-serving interests of the British. The 10,000-acre delta became mostly fields of cotton to feed the mills of Lancashire. Grain to feed the Egyptians had to be imported. (When I was there, Egypt was next only to Japan and the Soviet Union as the biggest importer of food.) Promises to leave Egypt were broken when war threatened the security of the Suez Canal, Britain’s vital shipping link to the east. International sanction for their illegal occupation was given when the French gave acceptance of British rights in Egypt in exchange for French rights in Morocco.

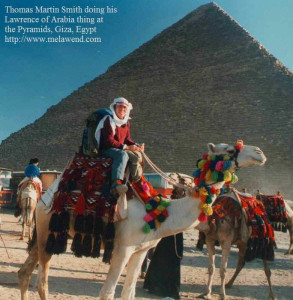

Ironically, it had been an Englishman, Thomas Edward Lawrence, “Lawrence of Arabia”, who helped mobilize the Arabs to victory over the Ottomans, arriving triumphantly with the Arabs in Damascus ahead of the British army, and then helping the Arabs in their strive for independence.

The Arabs finally rallied and went to war in an unsuccessful attempt to stop the establishment of Israel. The Egyptians blamed their puppet rulers and began a revolution in earnest. A military coup in 1952 ousted the playboy monarch and the British occupiers. The republic was proclaimed in 1953 and was led by a revolutionary commander who became its first president, Gamel Abdel Nasser.

So, as mentioned, I was guzzling formula in my crib when independent Egypt was reborn. And on this first day of 1986, riding the Desert Road to its capital, I turned another year older.

Just let yourself imagine this: New Year’s Day – you’re racing along the Desert Road on a heavy-laden motorscooter, crossing the Sahara Desert to Cairo! Last New Year’s Day, this journey still seemed like a dream to me; two years back I might have suggested that you were nuts if you had told me I would be here now. Well, I was here now, riding with the wind, getting honks and waves from the drivers of lumbering old trucks on a beautiful day on the road to Cairo.

Imagine!

I kept scanning the horizon for the peaks of the Pyramids. As we neared Giza, I saw powdery quarries of white rock. We passed a military area with barracks, target practice areas and empty buildings that were possibly used for anti-terrorist training. The road was converging with the Nile and there were trees here, the same feathery long-needled pine trees that I had seen outside Alexandria.

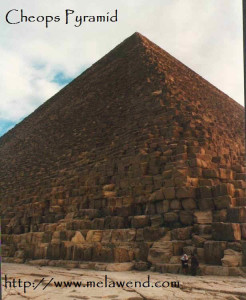

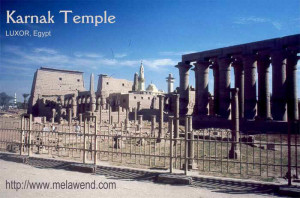

And there they were, at least the peaks of the two tallest Pyramids, rising up from the plateau on the western edge of Giza. The Desert Road came to an end at Shari al-Ahram – Pyramid Street – at the base of the hill that led up to them. I couldn’t resist – I turned Melawend right and went up the gentle slope at the north end of the 100-foot-high plateau, rounded a curve to the left and came immediately upon the base of The Great Pyramid of Cheops. It was mag-nificent! (Even if you were standing in the parking lot at its base.)

(Note: The Egyptian name is Khufu; Cheops is the Greek name.)

“Of course we were besieged by a rabble of muscular Egyptians and Arabs who wanted the contract of dragging us to the top – all tourists are. Of course you could not hear your own voice for the din that was around you…for such is the usual routine.” This was Mark Twain’s experience in 1867 as he told it in The Innocents Abroad.

“Come, my good friend.” a man said to me. “I take you on horseback around the Pyramids. Very cheap.”

When I took my eyes from off the Pyramid of Cheops, I saw the proliferation of horse-trotting, camel-riding, tourist-stopping guides who descended upon you with their offers. But there were not as many as Twain apparently encountered, nor were any of them offering to drag anyone to the top (a popular adventure in Victorian times, but climbing the Pyramids was now illegal). These fellows were in fact a rather orderly and a friendly lot. The cameleers were dressed in galabiyahs. (These were long gowns or robes. They are also known as jellabas, but any Egyptian I talked with called them galabiyahs). They also wore flowing scarves or bound headwraps. Some of the hawkers of horses and donkeys wore western windbreakers.

I needed to find a camp. Venzie had given me a map that showed Canal Street running off this road up to the Pyramids, which was also the main road into Cairo. But the map was in one of the saddlebags. I did not realize there were two Canal Streets, running parallel to each other. I rode up one beside a fetid canal. I stopped to get out the map but was immediately surrounded by half a dozen children who all began saying “Hallo!” and marveling at Melawend. I was concerned they might see the camera equipment at the top of the bag and so I just rode back to Pyramid Street, looking for the Canal Street that would lead to the camp Venzie had mentioned. I stopped about three miles on toward Cairo. Traffic of mini-buses, taxis and people walking the streets was getting thick. I pulled off. I soon had company.

“We’re on our way into Cairo to find a hotel,” said Don Travers. He and Murray Bielder, the two Canadians on the big BMW’s, had pulled up behind Melawend.

My budget allowed only for camping, so I wished them well. I knew that you had to check in with the local police when you stayed in a place so I backtracked and found a tiny station on Pyramid Street near the Pyramids.

“Welcome to Egypt,” said a lean young officer.

As I was getting registered, I met a young stocky German guy who had also brought his motorcycle to Egypt. His name was Rainer.

“It’s all perfectly mad here,” he said. “All these papers. It’s bullshit.”

The officer just smiled and kept scribbling.

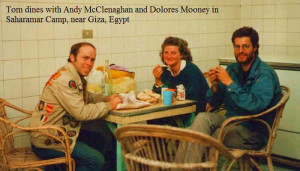

In a small tourist office, a jolly woman in a headwrap told me of the second Canal Street and the two campgrounds I would find along it. This second Canal Street was also a main road to Saqqarah. The first campground was about a mile and a half off the main road. The secondary road led through the worst squalor I had seen in my life – crude homes along a shaded canal that was shallow, polluted and reeking. A woman was washing clothes in it while another dumped filthy gray water into it. But as Melawend and I rode slowly along the bumpy road, the people along the way smiled and waved, not in the tourist-patronizing way but with the warmth of friendly neighbours – they continued to do what they had been doing. The clothes that people wore were amazingly clean, especially those of young girls who wore dresses that were almost florescent in colour. Still, I was apprehensive. A little boy leaned toward the road and said “Hallo…money?” I found the walls of Saharamar Camp but didn’t bother to look inside. Besides, I found it was too far to walk back to the main road to catch the mini-buses that took you into Cairo.

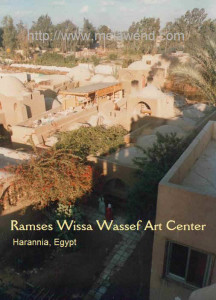

The second campground was at Harrania, about three miles off the Shari al-Ahram. This was Camping Salome – called Salma – a walled compound on a parallel road just off the main road. There were the same rugged vehicles here that I had seen on the Espresso Egitto. I went to a large, multi-coloured, heavily patterned tent, a sheik-style tent similar to one I’d seen in magazine article about an interview with Mohamar Ghaddafi. This tent served as a restaurant and bar. Here I met the owner of the camp, Sa’id Moussa, a trim handsome fortyish man who had been educated in Europe. He wore English equestrian boots. He looked at my growing portfolio of articles. Venzie and Don had told me they had paid three Egyptian pounds per day to stay here with their van.

“A quid…plus fifty for the showers… Shall we say, one-fifty per day?” Sa’id said.

I had my first home in Egypt.

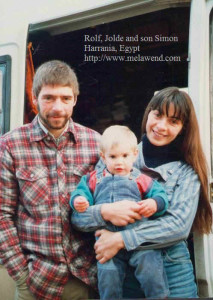

I set up camp under some pine trees off the parking lot and took a New Year’s Day self-portrait. While I was doing this, Rainer, the young German I met at the Police station, pulled in on his 500cc Yamaha dirt bike. He asked Sa’id about prices and he left. A short time later, a convoy rumbled in. They were all here! – the German couple and their bouncing baby boy, Garfield and his two companions, the couple with the white-painted army truck. We had a festive reunion. But conversation soon drifted into German.

I walked around the darkening camp and met a Dutch family. Reg, the father, was tall, lean and gray-haired, a younger version of the American actor, James Coburn. Lia, his wife, and their two young sons and little girl had been travelling in Israel and Jordan and were heading for Nairobi. Reg’s brother lived there. They were travelling in a dark green converted World War II fire truck that had six wheels. They were friendly and quiet-spoken, almost too kind, like people who all too easily have misfortune come their way

I walked over to the bar tent and talked with Sa’id about travel in the Sudan.

“It’s definitely not for your scooter!”

Rainer came back at this time and he talked with Sa’id. They spoke of people they each knew – other travelers. Rainer stayed. He was happy-go-lucky and always punctuated his speech with “perfect” expletives: “They are perfectly mad!” He was from a small town near Mannheim and planned to travel all over Egypt on his well-used 500cc Yamaha.

(It would die in Cairo, be dissected in camp and shipped back to Germany in pieces so Rainer would avoid loosing a bundle on his carnet.)

Salma Camp was a popular staging area for all manner of expeditions into Egypt. I felt safe here. (But when I turned in at night, from here on, I would put keys, wallet, passport and other small valuables in my pants pockets, roll up the pants and put them inside the foot of my sleeping bag.) When a tour group from St. Catharines, Ontario came in (remember the girl I met while photographing Big Ben?), well, I wanted to get out as soon as possible and see the real Egypt. First, I had to attend to my diplomatic mission in Cairo.

I awoke to culture shock the next morning, early morning. At 4:45 a.m., I was awakened by what sounded like a loud mournful cry. Booming on unseen loudspeakers, and seeming to echo from everywhere, were the rippling cries of muezzins: “Allaahu Akbar, Allaahu Akbar” (“Allah is Greatest, Allah is Greatest”). This was Adhan, the Islamic call to prayer.

“This is Islam,” I said aloud. “This is Egypt.”

It was a far cry from the jets of Athens. At least it was human.

At the intersection of the sand-filled lane that led to camp and the main road, ten of us piled into a mini-bus for the ride to the connecting bus at Pyramid Street. I was the only foreigner. There was a boy, an old man and a 50ish woman. The rest were young men, most of who wore scarves over their heads and long trench-like coats of various dull colours. Two of them wore galabiyahs. On the radio, I heard the first of the tinny, high-pitched instrumental music, and even higher-pitched female singers that would provide the familiar background sound of my journey from Egypt through Nepal. As we rumbled off, I sat with the old man and the boy in the back seat. They helped me take off my heavy daypack. It was 15 piastres for the ride. I passed a 25-piastre note passenger-to-passenger to the front, not expecting to see any change. The driver tucked the money into a pouch on the visor. Ten piastres were returned to me the same hand-to-hand way. I met with the same kind of friendliness on the equally packed mini-bus into Cairo.

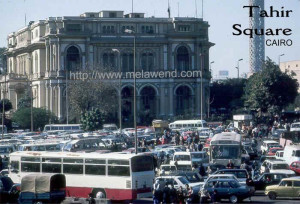

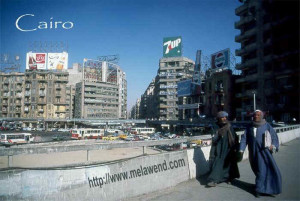

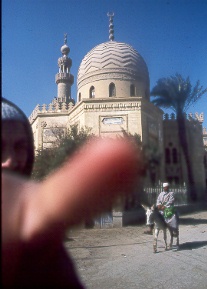

As with any new city, I was intimidated by what I saw. Here, it was the dirtiest, most crumbling and congested urban environment I had ever seen. The road buzzed with minibuses – Toyotas, Mazdas, VW’s, Daihatsu’s, Mitsubishi’s, and Nissans. Taxis were old black and white Peugeots or Hyundai Pony’s. There were dusty Chevy and Ford pickups, Chevy Caprice Classics and Mercedes with tinted windows. I thought: A car wash might do fabulous business here. Billboards were art, not photographs. For the first time, I saw animals in the streets – donkeys, bulls and goats. There were new unsafe-looking buildings. Three had primitive scaffolding around them – 10 stories of lumber lashed together. Buildings seemed almost monotone – all gray cement, mortar and red brick that would be plastered over. I saw the minarets of mosques and in a park, I saw the head of a giraffe poking its head up amid the trees.

We reached the terminal – just an open area that was crammed tight with mini-buses and milling people and vendors sitting on the pavement nearby with all kinds of goods for sale. The honking of horns, the droning of engines and the din of a thousand foreign voices assaulted the ears. This was Maydan-at-Tahir – Tahir Square – probably the busiest, dirtiest, most congested and convoluted crossroads in the world, I imagined. It was big and torn up and had no logical pattern or order to it – no wonder there was all that honking! Gray buildings that looked as if a stiff desert wind could easily topple them surrounded it. Garish billboards that were attached to them – including Coke, Fanta, and 7-Up – lent colour. It was strange to see Coke displayed in the familiar red and white logo but with Arabic words.

(Now, as the Coca Cola company celebrated its 100th anniversary, Coke was being sold in 160 countries after starting out as a tonic made by Dr. John S. Pemberton of Atlanta, Georgia.)

Cairo was chaotic and, to my Western sensibilities, dilapidated – I had an impulse to forget my mission and race up the Nile toward Kenya.

(But things were to improve tremendously in Cairo. In ten years – 1997 – a $1-billion French-built subway system, modeled on the Metro in Paris but done in polished Egyptian motifs, was opened in Cairo. It would eventually carry 1 million passengers a day, the same number of visitors that came here annually.)

“Change money?” came a boy’s voice. “Good rate.” His “r” reverberated.

I hunted for the embassy and found it on a side street that was blessedly quiet. But ignorant me, this was Friday – the Islamic equivalent of Sunday – the embassy was closed.

Back at Tahir Square, even amid all the chaos, I met Rainer. We went to a tiny restaurant that had sawdust on the white and blue tiled floor. We talked over bowls of rice, chickpeas, lentils and black things that looked like rabbit droppings. Food was cheap. At a bakeshop, Rainer treated us to baklava, which seemed a likely legacy from years of Turkish domination. This Egyptian variety was a triangular pastry wedge filled with a date paste – delicious! These would become a much-sought-after staple of my Egyptian diet.

We made our way the north side of Tahir Square, to the Egyptian Museum, a Neoclassic building of ochre limestone with a wrought iron fence. I knew only that this museum housed the world’s greatest collection of Egyptian artifacts. I had been annoyed in Paris and again in Italy at seeing huge bits of Egyptian heritage so conspicuously out of place. I shuddered to think of all the world’s national treasures imprisoned in foreign museums – but then how were nationals of a country to see artifacts of a foreign country if some were not allowed to be exported? (Make copies.)

All of Egypt’s movable treasures might have been lost if not for the man responsible for the creation of the museum I was about to enter. This was the French archaeologist Aguste Mariette who officially started the museum in 1858. In the mid 1800’s, Egyptian pashas were more interested in selling Egypt’s treasures than keeping them and so a lot of them ended up in European museums. Some of the best treasures went to Paris. In 1867, the French Empress Eugeni asked the pasha to give her the entire collection. The pasha referred her to Mariette, the museum’s director, who flatly refused her. He made it his mission to see that none of the museum’s possessions would ever leave Egypt. His mission had been successful to this day.

“Are you a professional photographer?” said a middle-aged man inside the admissions booth.

I knew that they wanted an extra 10 Egyptian pounds on top of the three-pound admission if tourists wanted to take pictures inside.

“I am,” I said.

Big Mistake,Tom.

“That will be 500 Egyptian pounds,” he said. And there was a big smile on his face.

“I won’t be taking any pictures,” I said.

I had lied.

I paid the three pounds admission and played dumb as I walked in. A guard stopped me.

“Do you have a camera?”

I should have said no. I had to check it in and leave it here. But I still had two more cameras in my daypack. Inside the museum, I saw lots of people taking pictures. Some were using video cameras.

“Egypt is perfect bullshit!” Rainer said.

Once inside, Rainer and I went our separate ways.

To conserve money, I had sneaked my cameras in. I also felt this was just a glorified tourist trap and that the fees were a big rip-off. But in the company of designer-dressed tourists, I had to remind myself that Egypt was a truly a poor country and it was worth far more than this bit of baksheesh you had to pay the government for the privilege of taking photographs of some of the world finest ancient treasures – not copies, the real McCoys!

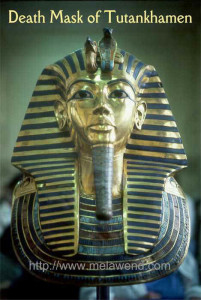

Here in this echoing cavern, were some of the greatest treasures yet found in Egypt. One could easily succumb to hyperbole in describing them in the detail many of them deserved. And I could have used a few days at least just to take it all in – there were over 100,000 pieces jammed into its dim halls and rooms. The museum relied heavily on natural lighting so that you had dark passageways, such as the one that was lined with shelves of sarcophagi, making it look like a neglected and over-populated mausoleum. 1700 pieces alone belonged to the Tutankhamen collection. An early 1980’s insurance estimate placed the total value of some of the museum’s major pieces at $13 billion.

For me, this was National Geographic territory. In unadorned displays, I saw so many artifacts that I had seen on the glossy pages of the Society’s magazine. So in a way, actaully seeing these artifacts was like living childhood fantasies. In Room 42, for example, I finally saw the badly split wooden statue known as Sheikh-el-Beled, a life sized image of a round-bellied man from the Old Kingdom (5th dynasty). In Room 32, I found the seated statues of Prince Rahotep and Princess Nofret, their limestone bodies looking unnaturally fresh from the 4th dynasty. Even then, Egyptians had a preference for fair skin, as the Princess was delicately painted yellow. A painted pink and white headband encircled her black-braided wig. The Prince was painted red with a Clark Gable moustache. The ancient Egyptians also flattered their pharaohs, especially those of the Old Kingdom, with statues that often bore little resemblance to the real person. They were considered gods and were depicted as beautiful and serene. Who was to say that Rameses II looked as good as Yul Brenner?

(Have you ever noticed that Hollywood stars are usually better looking than the real-life people they portray? Can’t you just see Tom Cruise playing the lead in this story?)

A young guard, lurking in one of those dimly lit hallways came up to me and looked around, not wanting to be seen talking to me.

“You want I take you to new exhibit, not open yet?” he said. “Very big exhibit.”

“Where?”

“You come.”

He led me to another unlit room. Are there no electric lights in this place? It was acrid with the dust of new plaster. There were big and small things draped in plaster-colored sheets, statues, I imagined. Some were uncovered but had boards leaning against them. He stepped behind one of the statues. He looked around again.

“You give me five US dollars,” he said.

“For what?”

“I bring you here. You look around. No one else. You have first look.”

Though his uniform made him look authoritative, like a policeman, his nervousness was growing.

“I have children. I work but I make little money,” he said. “You give me American money now.”

Why was I so naïve at to think he brought me here as a favour? Right from Alexandria, I had seen so many “working” people, so many people given some kind of job for the sake of having some employment, that wages surely had to be low. But I was dawdling and he was getting very anxious.

“Change money?” he said. “I give you good rate.”

I felt sorry for him.

Some tourists wandered into the room. He left to usher them out. I simply followed them.

Such a huge place filled with important historical artifacts could make you feel so small and intellectually intimidated, especially if you didn’t know much about what you were looking at. My mind felt unready for all this input – there was just too much to see here. I had to choose the obvious – what was at least somewhat familiar – and so I went upstairs to the second floor to see the Tutankhamen collection.

The main exhibit was in Room 4. There was a sign that said only 25 people were allowed at one time but there were at least 50 in the relatively small room. I maneuvered my way in and abruptly saw what was for many the quintessence of Egypt, the feature item on most Egyptian travel brochures – next to the Pyramids and the Sphinx – King Tut’s exquisite Death Mask. Photographs are wonderful things. They take you to places and let you see things you might never see in person. But it was humbling to see this icon of ancient Egypt in three dimensions, close enough to touch if it (had not been for the glass case that barely enclosed it). The image was one of serene, supreme power with a hint of arrogance. It was was awesome in its artistry and craftsmanship. I wondered if even today’s techno-superior craftsmen could duplicate this in all its shining splendor. And it was in showroom condition, as it were. This was truly a form of immortality.

I was puzzled as to why it stood so openly in the centre of the room (just to the left of centre, as I recall). There were few informative aids to tell you about all the things you were looking at in the room, including the mask.

I’ll look it up later; just take it all in for now.

The mask was life-size and made of beaten and burnished solid gold. You could see the reflections of tourists in its face. The eyebrows and eye lines were of rich blue lapis lazuli, the eyes themselves were quartz and obsidian, and the stripes of the headdress were of blue glass as was the inlay of the plaited false beard. On the headdress, there was a vulture and the cobra, side by side over the forehead. These symbolized the king’s sovereignty over Upper and Lower Egypt. The hieroglyphic text on the back of the mask contained a chapter from the Book of the Dead relating to mummy masks. It represented Tut as the sun god Ra in order to secure for him a solar afterlife. But I suspected that all this modern-day adulation was an unexpected and unwanted part of Tut’s afterlife.

Yet some of the incomparable riches he took with him were here. The wrapped body alone had been overlain with 143 pieces of jewelry, including 17 gold collars, 15 gold rings, 13 bracelets, a gold cobra, gold sandals, protective amulets, a sheathed solid gold dagger, gold finger and toe coverings. Even his penis had its own gold covering. All this was lying over the mummified Tut in the highly ornamented innermost (3rd) coffin, itself 296 pounds of solid gold.

In halls and other rooms, you saw more of the things Tut had indeed taken with him – the eight-foot-high canopic shrine, completely covered in gold leaf, which contained Tut’s mummified internal organs. There were the chariots, the guilded couches and the rigid, uncomfortable-looking gold throne where Tut had put his divine butt. Like everything else I had seen, it was highly detailed, and here in gold leaf on the back there was a relief of Tut sharing an intimate moment Ankhesenamun, his queen.

But Tut was minor king. He was just an eight-year-old kid when he came to power, and just eighteen when he died. I could only imagine the treasures the tomb of Ramses II must have surrendered to its plunderers.

The museum had been mind-boggling in the quantity and the quality of artifacts it held and their significance to Egyptian history. I had come totally unprepared for all this. If I had, I know that I would have had a greater reverence and respect for what I had seen. And I would have come back a few times. I had deluded myself into thinking I could read up on things just before I arrived: read up on Egypt while in Greece, check out India while in Kenya… I found that I could not afford guidebooks – specifically ones that were written independently (not by tourist boards) e.g., the Lonely Planet guidebooks. And I did not have the time, or at least did not make the time to visit libraries. The text in brochures was trite and biased and their photo illustrations omitted shadowy outlying details. So I was dizzy with cerebral overload by the time I left the echoing halls of the museum. Going back into the mind-blowing cacophony of Tahir Square did not help.

I would never really become use to the noise, the dirt, the crowds, the general chaos and the strangeness of the streets of Cairo (though seasoned by subsequent travels in other chaotic cites, I would love to go back!). I much preferred the view I got of this dusty city from a seat 590 feet up in the revolving restaurant (immobile then) atop the concrete lattice walls of Cairo Tower. From here, I looked southwest to Pyramids that rose at the edge of the desert over nine miles away. Looking the other way, across the Nile, I cringed at the bleak sprawl of dusty gray and brown city that had hardly a green leaf anywhere. It did however have “aerial farmyards” – families kept poultry, sometimes goats on their rooftops. I saw Nasser’s vast circular edifice, the broadcast station topped by a square office tower. It stood across the Nile at Balaq. The building contained 43 radio stations and 11 television studios and accommodated a staff of some 10,000 – more people than were employed in broadcasting by all the other Arab and African countries combined! I looked down on the spartan new hotels and apartments and the tide of congested buildings that pushed them up against the banks of the river. I shivered when I imagined myself in the midst of all that.

Cairo was a western name. For the Cairene in the street, and for most Egyptians, this was Misr which was also the Arabic name for Egypt. The name Cairo was derived from “Al-Qahirah”, a district of the metropolis that was the name of a city built here by the 10th century Tunisian invaders. This was misunderstood by medieval Italian merchants who took it and spread it throughout Europe as the name for the entire city. “Al-Qahirah” was adopted because media usage of the name.

As in many urban centres throughout the world in the 2nd half of this century, there was mass migration to the city – millions of fellahin moved to Cairo in search of jobs and a better life. The population now (1987) was 9 million – up from 600,000 in 1900. At 4.5 percent, Cairo also had one of the highest birth rates in the world.

There was no corresponding development in municipal services. It had decrepit public services and amenities, inadequate public transport, frequent power outages and an overblown bureaucracy. Almost a quarter of Cairo’s entire working population was registered government officials, working in the civil service and public sector companies. Decisions were delayed for months to decades. Multiple agencies were engaged to see plans through. Corruption was endemic due to poor pay – bribes were regarded as legitimate perquisites of office. College graduates, who applied for a government job, automatically got one, provided he or she did not demand useful work (this was unproductive work that paid about $60/month). There were too few commercial and industrial enterprises to absorb the flood of young educated people. So you had government offices that were full of young idle officials who spent much of their time drinking tea or coffee and making idle conversation with people waiting to see their superiors. These officials, in turn, employed an army of dependants who supplied them with refreshments, ran errands, carried messages or acted as bawabs in the ministerial lobbies. This resulted in relatively low unemployment – and employed people were less likely to challenge the political status quo. That was what was going on down there in that sprawling congested metropolis that was to be the “Paris of the Nile”.

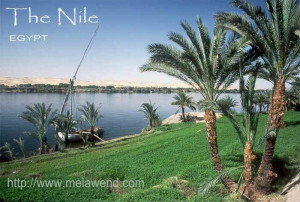

Standing in Cairo Tower, I then looked up the greenish-blue waters of the Nile – the river of Egyptian pharaohs, of daring explorers, the longest river in the world at over 4,000 miles. I followed it with my eyes to where it disappeared into the depths of Egypt. I was always nervous about the road ahead, yet equally anxious, now, to leave Cairo.

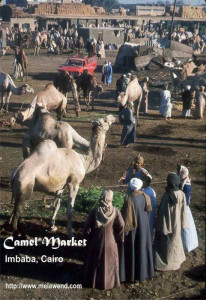

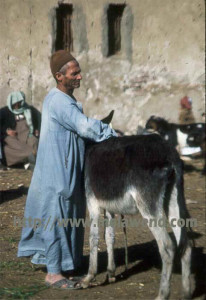

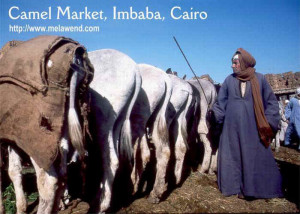

A few days later, Don, Murray, Rainer and I were taken by J. M. Scott-Harrison, an old friend of Don’s who now worked at the embassy, to the camel market in the Imbaba district. Except for the parked vehicles, it was a step back into time, to a wonderful, chaotic place of camels, donkeys and horses, of men puffing on hookahs and drinking chai. There were flea markets where you could buy many local items, from bright colored cotton fabrics to Egyptian daggers. I watched two Egyptian men, dressed in galabiyahs, as they haggled over coils of new rope.

The camels were the main attraction. Most hobbled about remarkably well on three legs. One foreleg was bound at the knee to keep the animal under control. One camel, however, had had enough prodding and parading and obedience performances. With leg unbound, he bolted out of the market. With a wide swinging canter, he made good his escape down the street. His cameleer followed in hot-tempered, fast-footed pursuit, slicing the air with a bamboo cane and what must have been Arabic profanity. Bystanders cheered the errant camel and made good sport of his pursuer. The cameleer grabbed up his galabiyah, jumped into the back of a compact Datsun camel truck and ordered the driver to take up the pursuit. The rebel was cornered and captured without a fight.

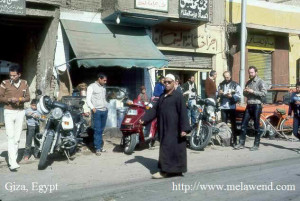

From time to time, I would touch upon the quieter local life in Giza. On the first Canal Street, I came upon some men in galabiyahs and headwraps who were sitting at a table on the sidewalk and playing a game that looked like backgammon. On man wore western clothes and sat in a wheel chair. He noticed that I was starring at the stump of his right leg.

“This was done to me by a land mine near El Alamein.” he said. “I was just a boy when it happened.”

Murray and Don took off for a tour of Sewa and El Alamein. The latter was where, after a week’s fighting, Montgomery defeated Field Marshall Rommel, “the Desert Fox”. It was one of the decisive battles of World War II that signaled the end of Adolf Hitler. But the carnage continued to this day.

Rommel had called the battlefield of El Alamein the “Garden of the Devil” – where his troops had laid millions of land mines. The British planted still more. Egypt had more live land mines than any other country in the world – almost 20 percent of the world’s land mines were buried in Egypt. With 17 million German, Italian and British mines, plus those of the Arab-Israeli wars buried in the Sinai, a total of 22.7 million mines were hidden beneath 284,000 hectares of Egyptian desert according to UN statistics.

(In 1993, 3 Israelis died while touring Sinai just 15 km from popular Red Sea resort of Sharm el Sheikh on a road clearly marked as safe – victims of mines planted by their own soldiers during the occupation of the Sinai. Six months earlier, two Americans honeymooning in Sharm el Sheikh were killed when their Jeep struck a land mine. Most casualties of mines are among the Bedouin villagers who lived near El Alamein. The International Committee for the Red Cross says that there are currently more than 119 million active mines scattered through 71 countries. The UN estimated 800 people were killed by mines every month, another 1,200 were maimed. Between 1981 and 1991, the Egyptian government cleared 11 million mines between Alexandria and El Alamein where resort hotels and luxurious houses were being built. The mines remained in the Bedouin hinterlands. Clearing the remaining mines was estimated at $200 million. In a 1997 report, 8,300 people had been killed by the forgotten mines since the 1940s (figure by Egyptian Foreign Ministry).

As we know, one of Princess Diana’s last crusades was to help rid the world of these lingering hidden destroyers.)

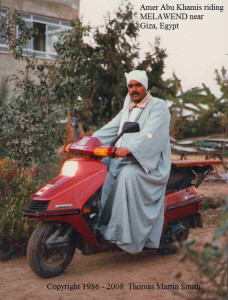

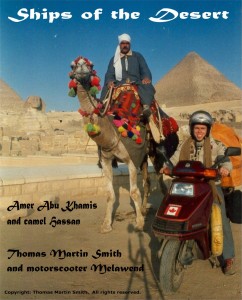

One day, a man came into camp who, to me, looked to be the image of old and modern Egyptian combined. His name was Amer Abu Khamis. He was more than just a cameleer at the Pyramids; he would become my best Egyptian friend. He looked a bit like a swarthy version of the Ernest Hemingway that Paris knew in the 1920s – the moustache, the strong rounded features, and the manly zest for life showing in his smile and his gestures. He was usually dressed in a fine-quality gray galabiyah and white headdress. Amer sought out tourists in the camps, not only for his business, but because he genuinely wanted foreigners to enjoy his country and to take back favourable impressions of its people.

“You come and we eat together at my home,” he said.

Riding Melawend, I would sometimes follow him as he rode on his camel, Hassan, through the crowded, dirty and confusing streets of Giza to his large house. We would sit on the floor in the living room and eat meals that often included camel meat, cooked by his lovely wife Samira who was always dressed in traditional flowing clothes. When he would have several people over, we would sit on the floor around a huge bowl of rice and meat and dip our hands in to get our fill. Amer would provide Egyptian clothes for guests and share drags on a large ornate hookah. When I would leave Cairo for side trips, I would leave my gear at his home. He had had a German guest who had gone to Somalia three years earlier and had not returned.

“As you can see, his things are still here,” Amer said. “I do not know if was arrested or what.”

On the walls of this room there were framed scenes of ancient Egypt painted on pieces of papyrus. Others had text from the Koran printed in Arabic. But what got my attention were the photos on the wall. They showed Amer at the Pyramids – one was an excellent black and white portrait of Amer with Hassan. Another showed Amer at a festive family gathering. He was wearing a white a galabiyah, a big smile on his face. His arms were spread wide. Another frame held an article from Expressen, “the daily newspaper of Scandinavia”, with photographs showing Amer with King Carl XVI Gustav and Queen Silvia of Sweden at the Pyramids where he took the royal couple on a tour.

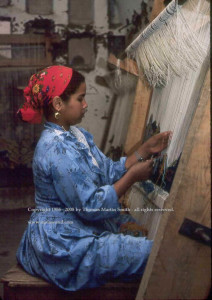

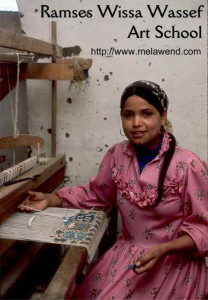

Amer would prove his friendship several times. Once was after I purchased three thick exquisite hand-made wool carpets very cheaply.

“How do I send these home?” I said.

“You must not send them by mail,” Amer said. “They will never arrive.”

But I thought I had a way to do it, possibly for free.

(We’ll get to the part where I take them to the Sinai and then to Alexandria to try to get them shipped home. But it was Amer who ultimately gave them to a tourist who would take them as luggage into Israel and then on to Paris where they would remain locked in someone’s apartment for over a year before they were finally shipped to the tourist in Canada. I would meet this tourist and her fiancé at the Valhalla Inn in Toronto and be presented with the carpets after their own odyssey. These carpets will take on significance as we go along… For now, I had found a trusted friend in Amer.)

As cliché as they are, how could one go to Egypt and not visit the Pyramids? But before you can touch those crumbling monuments to human engineering, you are welcomed in by many patronizing tour guides, as mentioned.

“Where are you from?” a guide asked.

I told him.

“Ah, Canada! Number One!”

I thought that if I had begun waving our flag, he would have personally carried me anywhere I wanted to go. But now who was being patronizing?

I assumed that the size of your wallet was estimated by the country of your origin. And to gain your confidence, the hawkers always had relatives living in your country. Based on the welcomes and the conversations with shopkeepers, cameleers and sellers of horseback tours, black market money exchangers and dealers in various tourist and personal services, it might have been assumed that half the population of Egypt had moved to Canada. There were brothers in Vancouver who were successful doctors, so many cousins in Montreal that now had French accents, and Toronto must have had an Egyptian equivalent of Chinatown.

This whole theory of the Egyptian / Canadian familiarity and bias was shattered however, when I said I was an American.

“Ah, America! Number One!”

And what if I said I was from Israel? I did not even try.

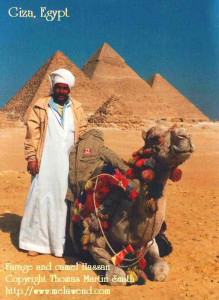

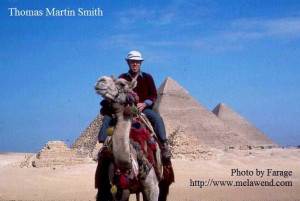

Before I met Amer, I negotiated a ride on a camel with a slim, dark young Egyptian cameleer in a white headwrap and a blue western windbreaker. His name was Farage. It would be unfair to the bargaining process and to the guides who depend on this work for their living to tell you what I paid. It was best to ask other travelers, or to look for the sign that was posted near the edge of the market at the base of the pyramids, near the Sphinx, to see a recommended fee schedule. If I could have afforded it, I would not have bothered dickering. After all, how many times in your life would you ride on a camel, let alone ride one around the Pyramids?

But I also can’t leave you hanging like that! (Besides, these were the prices in 1987.) I had heard prices as high as US$30 for an hour’s ride quoted to some tourists. An English guy told me he paid $20.00 for one hour on a horse. But that crude sign suggested an hour on a camel would cost about $1.50, a day would cost about $5.00.

(My suggestion: be prepared to bargain – that’s part of the mutual fun of it – and use your own discretion.)

“Money?” Farage said. “No problem.” Occasionally, he would turn and look up at me on Hassan, a bit concerned that he was doing well for me. “Are you happy?” “If you are happy, I am happy.”

He meant we could talk about money later. There was a rivalry between tour guides. Having customers in tow gave them pride among their peers.

Farage’s seven-year-old camel, (another Hassan) was lying on its stomach, its legs folded under. Farage motioned for me to get on. This was done almost as easily as you would get onto a horse. Hassan gurgled heavily and was about to turn his head toward me – I had heard camels had foul breath and were notorious for spitting. Farage imitated Hassan’s sound and Hassan heeled like a reluctant but obedient dog. Then in a flash, I was hurled hard forward and then backward as Hassan got to his feet. I think some cameleers love to see the reactions on their customers faces at this bit of local culture shock. Farage smiled. He then led me on what must have been a tour that went back to ancient times: a slow, plodding circuit around the main pyramids. We went down the ancient causeway to the Sphinx and back, and then out to the dune where you got a view of all nine pyramids. Out there, I met Farage’s father, Abu Awash, who posed against this backdrop as his own camel kissed him. Farage gave me a white headdress and I did my Lawrence of Arabia thing on Hassan for my own camera.

(But be aware that cameleers are not the best picture-takers – in the photo, Hassan’s legs were cut off below the knees. It might be better to have someone in your party take the photos.)

In the end, we settled on a price that was far less than what he asked. And like anyone who has worked for someone, Farage sought a written reference – I was pleased to write one out on the back of one of my business cards.

In Charlton Heston’s book, The Actor’s Life, I had seen a photo of Heston and his wife Lydia sitting atop the Pyramids (photo taken by son Fraser) in 1965. Heston said this climb was something he should have done ten years earlier. He said that it was “very special, putting my feet in the troughs worn there by the millions of feet that’ve climbed before me in the five thousand years since it was built, polishing with the sweat of my palm the gleaming handholds men have worn in the time-carved stone. The view from the top was deeply stirring for us…”

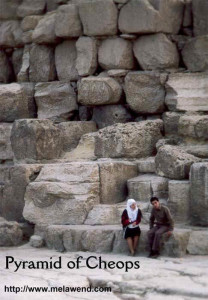

As mentioned, it was now against the law to climb up the Pyramids – tourists had died after they slipped and fell down the crumbling blocks. But Farage encouraged me to climb one of the lesser pyramids of the queens for an elevated shot. This was one of the three pyramids beside Mycerinus’ pyramid, the 3rd of the three great pyramids. I climbed the one on the right facing Mycerinus. Though they looked almost indestructible, upon closer examination, the pyramids were slowly turning to dust. Grains fell with each of my footsteps. I slipped twice. While Farage squatted below, I got my photographs. I tried to envision the Pyramids as they were, originally covered with polished Tura limestone with joints so fine they could hardly be seen. They must have been truly awesome in their white virgin beauty, before they were stripped.

(PHOTO – for scale, note two people sitting at the base of the pyramid, lower right. Enlargement of section showing couple below.)

Of course the massiveness of the three largest Pyramids is one of their greatest attractions. For this narrative, I’ll focus on the Great Pyramid of Cheops as I would later go inside it. Since it was completed around 2500 B.C., it has been vandalized, gawked at, bored into, measured and subjected to many theories as to its construction. I could fill the next several pages just with tales of the dealings with this massive pile of stone blocks.

Here then are just some of the details of its construction:

- It was 481.4 feet high when it was covered with a smooth polished casing of Tura limestone and capped by an apex or a pyramidon of granite, guilded to catch the first rays of the sun. These were stripped off by thieves over the centuries. It now stands 450.4 feet high (the pole on the top indicates its true height) so that we now see 201 tiers of blocks rather than a smooth triangle. It is the height of a modern 40-story office building.

- The base of the Pyramid covers over 13 acres, or about 7 midtown blocks of New York City, and was leveled to within a fraction of an inch.

- It is comprised of limestone and granite blocks, weighing from 2 to 70 tons each – 2.3 million of them!

- Each side measures 746 feet – 2.5 times the length of a football field.

- The sides are oriented almost exactly in line with true north, south etc. (the error is just over 5 feet, so the corners are almost perfect right angles).

- The sides rise at a steady incline of about 51°54′.

- Many of the stones were quarried right from the Giza plateau, using copper tools.

- It was not built by slaves, as Herodotus claimed. (Herodotus was a historian who visited the Great Pyramid in 440 B.C. His History is the oldest surviving comprehensive account of Egypt.) The Great Pyramid was built by teams of skilled laborers on three-month hire, supplemented by a permanent work force of local quarrymen. Other crews cut limestone and granite construction blocks at Tura and Aswan and transported them across or down the Nile to the building site. There was housing for 4,000, suggesting large and permanent administrative and supportive staff. Herodotus did say that it took 100,000 men working a three month shift, a total of 20 years to erect the Great Pyramid, and 10 years to erect the causeway and ramps which served as a form of scaffolding.

- Blocks were dragged via a limestone causeway on a wooden sledge by workmen pulling ropes while others oiled the runners to lessen the friction.

- The inner chambers were built first, and then stone blocks were packed around them. Then came the casing. The fit between the blocks remains so fine that you can not pass a razor between them.

- The white limestone casing blocks came from Tura, now a suburb of Cairo. The highly-polished casing alone would have covered 22 acres.

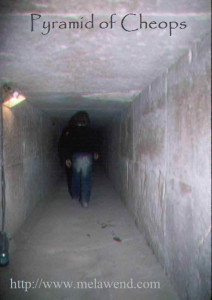

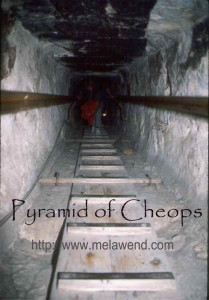

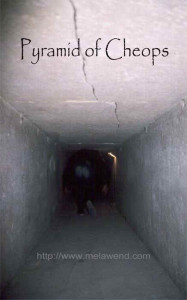

I would later go inside the Great Pyramid (you bought your ticket at a kiosk at the edge of the parking lot at the base of the pyramid). The entrance was a large hole in north face 55 feet up from ground level. This hole was made in the latter part of the 9th century by Caliph Ma’mun, the son of Harun al-Rashid of Arabian Nights fame, because he mistakenly believed the Pyramid contained hidden treasure (which it did not, having been robbed of its contents long before).

Inside was the tunnel that Ma’mun had chiseled out until it connected cut the Descending Corridor. This tube originally stretched downward 345 feet to an unfinished chamber that was about 150 feet below the base of the Pyramid. Herodotus, said this chamber was subject to flooding, so Cheops decided to put his chamber higher. He had a hole cut in the roof of the Descending Corridor about 60 feet from the entrance. The Ascending Corridor was built at a 26° gradient and was approximately 129 feet long. So you crouched and walked like a duck down through a dark channel that was 3 feet 5 inches in width and 4 feet 5 inches in height.

I began to sweat in the dusky humid air. Then you went up into the Ascending Corridor in the same fashion. You come to the Grand Gallery – a 153-foot-long and 28-foot-high narrow passageway made of polished limestone. At first, the blocks rose vertically then layered out, forming a corbel vault. As mentioned, it was said that you could not pass a razor blade between the massive blocks. I did not have a blade but I did have a piece of paper. I put the crumpled results of the experiment into my pocket, just as the girl ahead of me had done, and continued walking upwards, deeper into the Pyramid.

You climbed via a rather rickety wooden ramp up the gallery’s length to an anti-chamber and then to a low, narrow passage that led to the King’s Chamber. At this point you were 139 and a half feet above the plateau outside. To get into the chamber, you had to crouch down again and walk through a short tunnel that was about four feet high and four feet wide.

Then you found yourself inside a large dark box (19 feet high, 34 feet long and 17 feet wide). It was made of pink Aswan granite and was lit by one bare bulb. The ceiling was also made of ominous slabs of stone. I didn’t know it at the time there were 400 tons of stone above my head. This was comprised of nine slabs arranged into five separate stacked compartments built to eliminate any risk of the chamber collapsing under the weight of the pyramid.

Near the west wall of the chamber was the empty granite sarcophagus that once contained Cheops’ body. The upper left-hand corner of the sarcophagus had been severely chipped away by tourists. And three feet above the floor, you saw two holes, air shafts, that lead all the way to the outside of the pyramid. These were for ventilation and for the pharaoh’s spirit to come and go.

In this gloomy atmosphere of impregnable enclosure and death, you could imagine this as the set of an Egyptian horror film. Would you want to be in here alone? Alexander the Great was reported to have been so. In 1799, Napoleon Bonaparte visited the Pyramid with the Imam Muhammed as his guide. Napoleon asked to be left alone in the Chamber. When he emerged, he was pale and would not speak of his experience. He would later only hint that he had received some presage of his destiny. At St. Helena, near the end of his life, he appeared to have been at the point of confiding his experience to Las Cases, but instead he shook his head, saying, “No. What is the use? You would never believe me.”

There were only three other tourists with me in the King’s Chamber and I waited for them to go. I wanted to be alone where Cheops had once been. By being alone in a specific place, I felt I could be closer to its history. This was not the case in the King’s Chamber. I suddenly felt claustrophobic and cut off from everything except this gloomy room. It felt like some transition room where you waited between unknown worlds. It felt like my soul was exposed and I was within moments of facing my own mortality. It was frightening sensation. Spooky, to say the least! Lay it to a legacy from Hollywood, but I got a distinct feeling that if I tarried, some section of the floor would suddenly open up, I would fall into a deep pit and the section would close over me. And I would never be heard from again. I did not want to take any chances. I took one more look at the around the spartan chamber and headed out, just as more tourists were climbing up the Grand Gallery.

I came out grateful for the opportunity to have been in the room where one of the greatest pharaohs had been laid to rest. Just as in Bath, I rejoined tourists, having emerged surrealistically from the depths of immortal history to the noise and haste of the transient present.

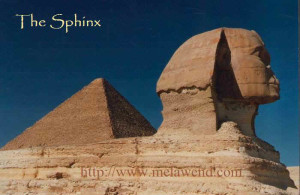

I spent time just gazing at the Sphinx, that cliché recumbent lion with a mutilated human head. It was 66 feet tall and 240 feet long. The face was that of Chephren, (Khafre – 2589 B.C. – 2566 B.C.) Legend had it that Napoleon shot off the nose because he thought the Sphinx’s smile was mocking him. More likely it was the Mamelukes who used it for target practice, scoring not only on the nose but also obliterating the beard. Or was this done in late 14th century by Saim-el-Dahr? He was a religious zealot who regarded the mere presence of the statue as pagan and idolatrous. English Colonel Richard Howard-Vyse bored holes into the Sphinx to see if it was hollow. One way or another, it had been abused by humans and eroded by wind and water. It was in rough shape. At least the klaft, (a royal headdress that fit behind the ears and was made of striped cloth) was still intact and you could see faded red colouring in some of the stripes.

(The popular theory was that it was built in Chephren’s time. But a 1993 NBC television program, narrated by Charlton Heston, presented a different theory. American mystic, Edgar Allen Cayce, who died in 1945, claimed to have seen a secret chamber in a vision, a vision of buried secrets. The program was produced by author and tour leader John Anthony West and two authors, Graham Hancock and Robert Bouvall (best-selling book The Message of the Sphinx), who pointed to scientific facts to support some of Cayce’s contentions. From seismography, geology and astronomy, all have argued that there is ample reason to believe that the sphinx was built about 10,500 BC (was much larger and was since recarved) and that there is a hidden chamber beneath the Sphinx’s paws – Cacey called it the Hall of Records – and that its contents may contain the secrets of Atlantis.)

The Sphinx remained an intriguing mystery – one that I could not touch because it was closed off to the public for yet another obscene attempt at restoration. Like the Leaning Tower of Pisa, it seemed no one knew how to save it.

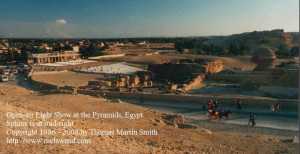

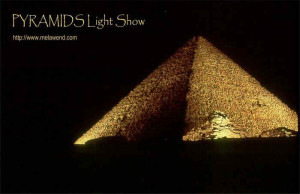

I would come at sunset to get silhouette shots of the Sphinx and take in the Light Show. I hid in the gravelly hills opposite the Sphinx and took my time exposures as these ancient wonders were brought to theme-park life under bright colored lights. Then came the sounds of ancient horns and a crescendo of music evocative of the approach of something possessing absolute power. The face of the Sphinx became bathed in golden light. A deep-voiced narrator began to tell the story.

“You have come tonight to the most fabulous and celebrated place in the world. Here, on the plateau of Giza, stand forever the mightiest of human achievements. No traveler, emperor, merchant or poet had trodden on these sands and not gasped in awe…”

*****************

(Now, dear reader, I’ll depart here from my narrative a bit to quote you exactly how I recorded this evening here both from tape and notes. We all have our own ways of recording events in our lives. For a journey such as this, memory would not be enough because it is often too selective and prone to error. As mentioned in the Prologue, I accumulated over 10,000 pages of notes (including over 2,000 pages written during the journey), photographs and other data and over 60 hours of audiotape. Here, then, is a portion of my collated journals and recordings, enclosed by >>> and <<<… This comprises the next one and a half pages.)

>>>Sun is setting. Sliver of a moon. Orange at horizon blends into the indigo blue sky. See the silhouette of the Sphinx.

Sometimes I can’t believe where I am… the Temple of Poseidon, the Matterhorn, Norway, the Pyramids. .. Takes your breath away. I think I’m finding what I want to do. It’s the people too. They are inseparable from these spectacular locations. So many things in common, yet so different. And the contrasts yet to come, such as Japan.

Everyone is on the take here. I came back up after having the Kofta – took photos of cameleer on adorned white camel – he wanted $5.00 US. I gave him about 25 cents. Light Show is off. I wander around.

Then it’s around 6:00, dark. Hear small dogs barking in distance. At the Sphinx, saw fellow puff on cigarette, saw the glow of it. People walking along road beside the Sphinx. No lights on it. Open-air theatre with white seats. See a lot of camera flash going off by Sphinx. Sitting behind a little building in the side of the sandy, gravelly hill – and talk softly as I record this. Small window, light on inside. Three holes in top, no light visible. Stone wall beside Sphinx – camels coming down cast faint shadows on the wall, a little dust is kicked up. Moon is really moving.

I hear a cart go by. A cat jumps up onto the roof of the small building. See lots of stray dogs. The Light Show begins – must be 7:00 p.m. Dramatic music again. Lighting the Sphinx is dramatic. Hear myself taking photos (on tape). Narrator (of the light show) – talking about the origin of man. Chephren in blue, like a diamond, Cheops in gold, like a huge mountain of gold in the night, pointing to the starry heavens. Seems like light is coming from inside. I hear the British narrator say: “At the foot of these mountains of stone, everything becomes minute and insignificant.” I walk. Hear me taking photos. (on tape) I walk to the Pyramids. Going up paved road. Overcome by the sight of the illuminated Pyramids. Puffing. Two Arabs came up, startled by me, stared, took off. I’d left camera cable by the wall while shooting the Sphinx. I went down. Glint of light on cable – found it! Incredible sight: Cheops in gold! Shadows on every stone. Chephren now in Gold. Smaller one in blue, like a light inside. Air is about 60 degrees. I’m all by myself. Not supposed to be here. Incredible. I have to keep kicking myself. Looking back over Cairo – looks small lit up, not like Toronto. 14 million in Cairo area.

Time to leave. Heading up and away from the Sphinx. Hear my footsteps, a little crunching of gravel on pavement. Walking by bank of lights on flank – wait until they are off. Looking at Chephren, moon is just to left of the peak and a little below it, crescent is pointing toward the pyramid. Get the atmosphere, music in background. Little pyramids being lit. Weird being up here. Lights now off Cheops. Now all dark, but Pyramid, so perfect shape picking up ambient light. Right beside Cheops now.

(Not mentioned was my passing the Solar Boat Museum behind the Great Pyramid. Environmentally controlled, it housed a re-assembled wooden boat found in one of the 100-foot-long boat pits near the pyramids. I then walked between the Great Pyramid and three lesser pyramids on my way to the parking area. According to Herodotus, the middle pyramid was for his daughter, and the last one was for Henutsen, one of his wives, who may have been Chephren’s grandmother. My notes continue…)

Have to watch where you walk – horses, donkeys, and camels… you know. Must fake my way past guards. Road is blocked ahead. I can hear guards. Talk with guards.

“The road is closed here, to drive?” I said.

“Yes.”

“I see.”

“Where you going?” he said.

“To Giza, I go down the hill?”

“You go down the hill to the bus.”

“Thank you. Shukran.”

The guards are turning cars around, including a Rolls Royce. I note a little further on that I had no fear being around the Pyramids alone.

I pass a café near the entrance of the Police station. There are several people here, walking. A mustachioed young guy approaches me and asks me where I’m from.

“You have Canadian dollars, cheque? Cash money. Good rate,” he said.

“Sorry, I have already changed all my money,” I said as I start to walk away.

“American dollars?”

I continue along the road. I feel that people here take a course on how to approach tourists. They all say, “Welcome, Welcome. Where are you from?” This might tell them what currency you have, and how much. Another young guy approaches me.

“You go tomorrow Saqqarah?” he said.

“No. I’ll be going back to the Pyramids.”

“You sleep at the Pyramids?”

“I wouldn’t mind trying it.”

“You have sleep?”

“I’m staying with friends.”

I begin walking away and he walks with me.

“Okay, if you come to Pyramids tomorrow, go to Saqqarah, my name is Kamil. You come see me. I have camel, horse to Saqqarah.”

“A horse to Saqqarah?”

“Yeah! And also the camel.”

“How much for the horse?”

“Are you a student?” he said.

“Yes.”

“Fifteen pounds.”

(I had already met an American who had paid $22 US for the ride.)

“How long does it take?” I said.

“Five hour. Two hour go. Two hour back. One hour you look at my pyramid and the mummy and the temple, you sit down, you drink and go back.”

“I meet you here?” I said.

“Yeah. Meet in my shop.”

“Okay.”

(This is now a happy man.)

“You want, okay, you come.” he said.

“Okay.” I said. I’m trying to walk away.

“You have friends, they come?”

“Maybe.”

“Okay, you tell them to come Saqqarah tomorrow, maybe.”

On impulse, I stopped at a shop at the base of the hill you go up to the Pyramids and bargained for a galabiyah. They asked 25 pounds. I offered 15. 18 come back. I stuck with 15.

“Okay, you take.”

I ride back to Salma Camp on the bus. I talk with young guy who works as security guard at a beach hotel in Hurgada. Likes blonde-haired girls. A 10-year-old boy smokes a cigarette.<<<

(Thank you, dear reader, for indulging me. I hope you liked it. Now back to the narrative about the Pyramids. There are some people I’d like you to meet.)

At first it seemed ridiculous, almost sacrilege to commercialize these ancient wonders but this garish bit of high-tech sight and sound began to work on you. Seeing the images of the real Pyramids and Sphinx bathed in coloured lights in the blackness of night, made them look as if they were floating in space. The Great Pyramid looked like a glowing mountain of gold bricks. The music and the voice (alternately in English, German, Italian and French) were loud and echoing. From where I was sitting, it seemed to be coming from everywhere. I emboldened myself, set up my camera and tripod and got to work.

I would visit this ancient site often. It cost nothing just to walk around. The site was big and open, so it seemed there were never a lot of tourists around. But the wonder of the place was heart-breaking to experience alone.

Don and Murray came to stay at Salma camp and I brought them here for this clandestine experience of the Light Show. But my greatest joy in sharing this event came after I met a girl with… how shall I say it…with possibilities. Two patrol guards caught us.

“You come with us. Big trouble,” said the younger one.

The taller superior, whose head was wrapped in a flowing white headdress, was more sympathetic and spent several minutes telling us the history of Egypt. I sensed that it was because of this girl that we were not kicked out, or worse. Then he and his charge left us to enjoy the rest of the show.

I could see only exciting times ahead for this girl and me.

Her name was Audrey. She was blond-haired, buxom Aussie who had come into camp one day in tears. I had seen her walk to the restaurant/bar tent with a look of anguish, anger and wounded pride. She looked a bit like the now-late American actress, Elizabeth Montgomery, especially in her post-Bewitched days – that is to say Audrey had the look of a beautiful, strong-willed and yet troubled woman.

Sa’id escorted her to a small room in a low building near the wall of the compound. She was given those quarters. She was travelling alone in Egypt, which was a risky thing for a blond-haired girl to do in virtually any Arab country. Males dominated Muslim society, and a blond-haired girl was particularly appealing to them, especially when she had such full figure that even heavy clothes could not hide.

Audrey had been invited out to dinner by an Egyptian but, by her account, she was taken instead to his home where his family went into other rooms. He did not allow here to leave until 5:00 a.m. I never really knew if she had been raped – she wouldn’t say – though I suspected she had. She told me about being pressed up against some lockers in her high school days by a few guys, but again she gave few details. I was left to fill in the blanks. There was a lot to this girl that I didn’t understand.

She had to make calls home to Sydney and I had my diplomatic mission to attend to in Cairo. We shared a mini-bus and visited our respective embassies. At AUS$590 per night, she had blown her budget by staying three nights at Mena House at foot of the Pyramids, on road leading up to them from Pyramid Street. This was part of the Mena House Oberoi Hotel, one of most celebrated hotels in the world and one of the most expensive in Egypt. Helen had to request that money be wired to her.

We began enjoying each other’s company. I knew the perils of walking around in Cairo traffic, so I took her hand when we rushed across streets. We jokingly referred to this traffic-dance as our “Cairo Hustle.” On our way to a telephone exchange, a tall young Egyptian guy purposely elbowed her right breast as he and his friends passed by in the opposite direction. As the jerk and his friends laughed, Audrey restrained me as I went to turn on him.

In the gentle late afternoon light, we shared tea in the open at café beside the Nile. Can you imagine this romantic ambiance? We walked some more, but at a relaxed pace. She continued to hold my hand. After I tumbled out of the minibus back in Harrania, with the grace of a graduate of the Red Skelton School of Falling, she laughed uproariously. It was good to see her happy.

I was amazed when she talked of building a house by herself – she knew how use power tools! We seemed to share some of the same talents and dreams. She had a week or so left and no specific plans. It seemed natural to ask her to travel with me.

It was the night of the Light Show. Some cameleers acted as guards to catch non-paying patrons.

“Get down, like this,” she said. Audrey suggested a way for us to lie prone and retain a good vantage.

But we were caught anyway. The two guards I spoke of earlier came up to us. She didn’t crumble.

“We’re not going anywhere with you.” she said to the younger guard.

I admired her spirit and her strength of character. After the guards left, I told her more about my journey.

“How would you like to go around the world with me?” I said.

“Sure!” she said with only a slight hesitation.

I was thrilled!

(Dear reader, why are you not surprised?)

“Yes, now they can say the black sheep of the family is doing something good,” she said later.